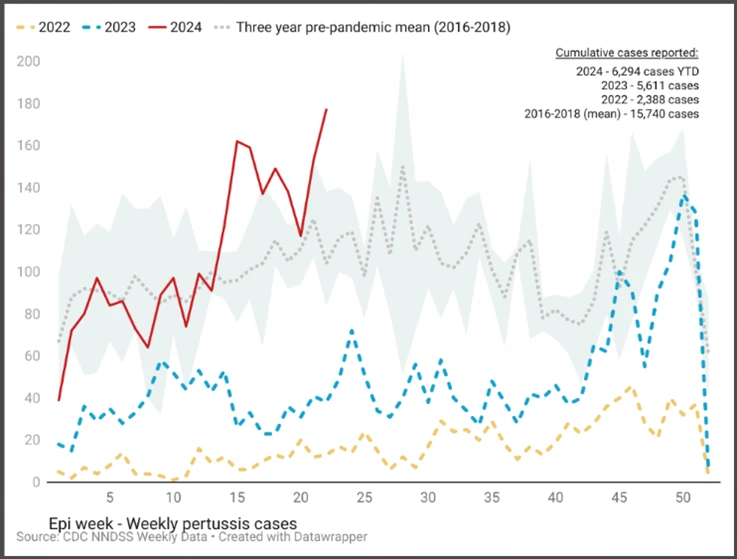

Also known as pertussis, case counts have been rising for more than a year, with some regions already far exceeding their 2023 totals

Cases of pertussis, also known as whooping cough, are currently on the rise around the globe, a trend that has intensified throughout the first half of 2024. As an acute and highly contagious respiratory disease with long-lingering symptoms, whooping cough places a particularly heavy burden on families with infant children and has the potential to cause substantial disruption due to work and school absenteeism.

European Union, for instance, reported more than 32,000 cases of pertussis in the first three months of 2024, which already exceeds the 25,000 cases reported for all of 2023. The EU’s case counts are now approaching its most recent pre-pandemic peak, reported in 2019.

Similar situations are being reported in countries and regions on other continents. Just last week, cases in Quebec hit nearly 3,500 – 33 times higher than the total number of cases in 2023 and well above the Canadian province’s pre-pandemic peak of 1,269 cases in 2018. Surges above pre-pandemic peaks were also reported in Russia and China; in the case of the latter, just two months into 2024, counts have already reached more than 32,000 cases, compared to a total of approximately 30,000 cases in the entire 2019 calendar year.

From a global perspective, cases started to increase in mid-2022 and, according to a recent Intelligence Report from BlueDot, are on track to exceed – or have already exceeded – case counts from last year. As a worldwide endemic with a cyclical pattern of peaking cases every three to five years, scientists are gearing up for epidemics as cases continue to rise.

Whooping cough: A history of ups and downs

In the early decades of the 20th century, whooping cough was the most frequently diagnosed disease in American children, with over 200,000 cases per year — before vaccines helped stem its spread. Pertussis is caused by the bacterial pathogen Bordetella pertussis, its primary symptom being a severe cough that can last up to three months. First isolated in 1906, it is primarily spread by air through coughing or sneezing, with an incubation period (time for symptoms to emerge) ranging from one to three weeks. Young children, especially infants under one year of age, have the highest incidence of whooping cough, and they are at the greatest risk for severe disease and complications, including penumonia, seizures, encephalopathy, and death.

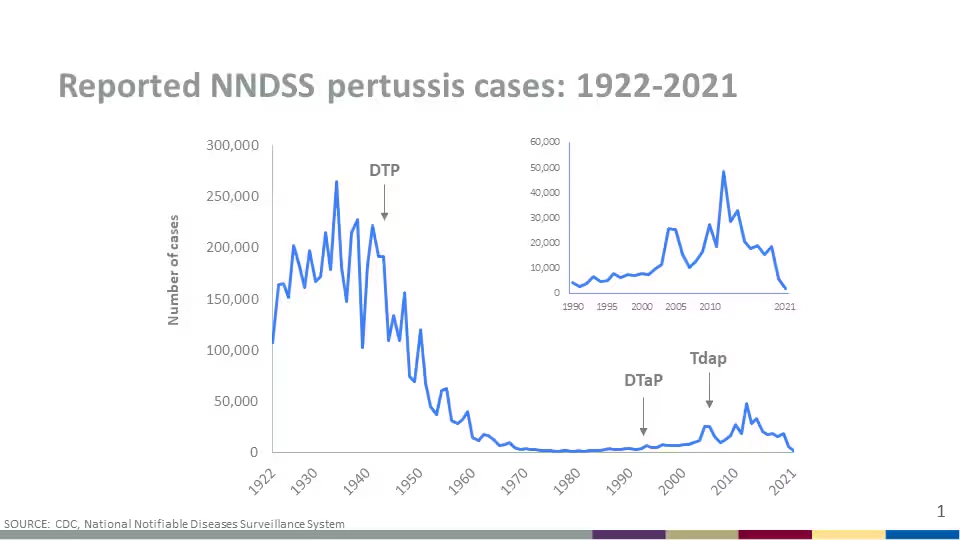

The development of a whole-cell vaccine (DTP, short for diphtheria tetanus pertussis) in 1948 proved extremely effective in combatting morbidity and mortality of pertussis, as the US saw a 150-fold decrease in incidence by the early 1980s. But the occurrence of that vaccine’s side effects, including prolonged crying and febrile convulsions, along with suspected links to neurological side effects, led to the broad adoption of an acellular form of the vaccine (DTaP), which is less likely to trigger a mediated cellular immune response and is associated with a lower frequency of adverse reactions.

However, differences in the acellular vaccine’s mechanism of action resulted in waning immunity after 2 to 3 years, leading public health authorities to recommend regular booster immunizations (Tdap) to mitigate the loss of protection.

In the early decades of the 20th century, whooping cough was the most frequently diagnosed disease in American children, with over 200,000 cases per year — before vaccines helped stem its spread. Pertussis is caused by the bacterial pathogen Bordetella pertussis, its primary symptom being a severe cough that can last up to three months. First isolated in 1906, it is primarily spread by air through coughing or sneezing, with an incubation period (time for symptoms to emerge) ranging from one to three weeks. Young children, especially infants under one year of age, have the highest incidence of whooping cough, and they are at the greatest risk for severe disease and complications, including penumonia, seizures, encephalopathy, and death.

The development of a whole-cell vaccine (DTP, short for diphtheria tetanus pertussis) in 1948 proved extremely effective in combatting morbidity and mortality of pertussis, as the US saw a 150-fold decrease in incidence by the early 1980s. But the occurrence of that vaccine’s side effects, including prolonged crying and febrile convulsions, along with suspected links to neurological side effects, led to the broad adoption of an acellular form of the vaccine (DTaP), which is less likely to trigger a mediated cellular immune response and is associated with a lower frequency of adverse reactions.

However, differences in the acellular vaccine’s mechanism of action resulted in waning immunity after 2 to 3 years, leading public health authorities to recommend regular booster immunizations (Tdap) to mitigate the loss of protection.

Back to the future: Cases rise in US, UK

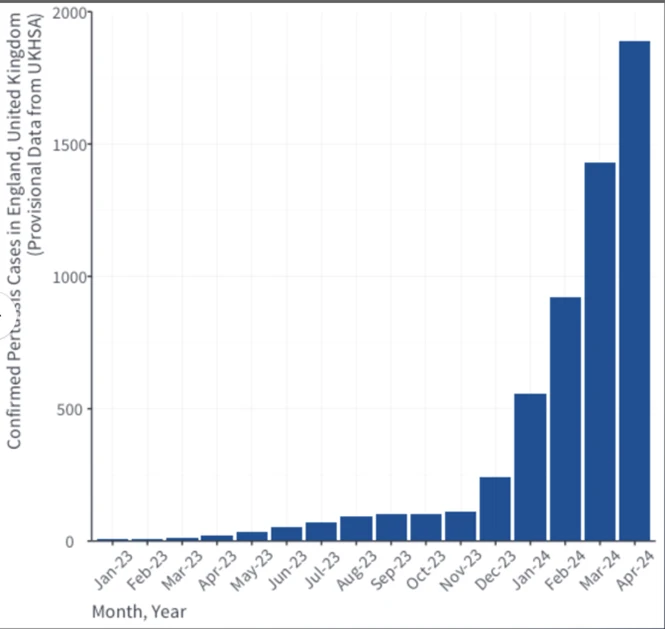

“Like many other vaccine-preventable diseases, whooping cough is a case of ‘back to the future,” says BlueDot’s head of surveillance Dr. Mariana Torres Portillo. “Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, we expected to see a resurgence of many diseases, and pertussis is not an exception, but it is really worrisome that previously well controlled pathogens are representing a challenge” From Asia to Europe to North America, cases of pertussis have been on the rise, with recent evidence showing sharp increases in 2024. The UK Health Security Agency has seen monthly reported cases skyrocket from around 500 in January 2024 to nearly 2,000 in April. Within the first half of 2024, there have been 4,793 cases, in contrast to a total of 858 cases in 2023. Similarly, 6,294 cases of whooping cough have been reported in the US, exceeding the cumulative counts for both 2022 and 2023.

Whooping Cough: 4 Top Takeaways

1. Pertussis rates resurge around the world. In nearly all corners of the globe, incidence of whooping cough has rapidly increased.

2. Multifactorial mechanisms. Waning population immunity, gaps in primary series and booster vaccine uptake, and declining vaccination coverage, combined with increased post-lockdown exposure, are some of the drivers of disease spread.

3. Protection against pertussis is paramount. Vaccination against this highly contagious pathogen has substantially reduced serious illness and death, which are most common in infants.

4. Innovation in inoculation. Current vaccines provide defense against pertussis with fewer adverse effects than before, but with immunity waning after 2-3 years. The next generation of vaccines now in development aim to provide longer immunity.

Reasons for resurgence

The reasons for whooping cough’s resurgence are multifactorial, and they include the COVID-19 pandemic. When protective measures to minimize coronavirus transmission were adopted, there was decreased exposure to many other infectious diseases, including Bordetella pertussis, which resulted in a lower number of cases. But the pandemic also led to a diversion of resources, laboratory tests, disrupted supply chains, and ultimately a decline in immunization services against pertussis and other pathogens. This was further exacerbated by growing vaccine hesitancy and consequent declines in vaccine coverage. As the lockdowns have been lifted and people have resumed their pre-pandemic lives, many individuals are partially or completely unprotected against pertussis.

In addition, research has demonstrated that the acellular vaccine, while preventing serious illness, does not prevent infection and colonization with the B. pertussis pathogen. That means individuals can become asymptomatic carriers of the disease, which also contributes to the trend.

Warding off whooping cough

The current acellular vaccines remain the safest and most effective means of mediating outbreaks and fatalities due to pertussis. “While no vaccine is 100% effective, it is the best resource to prevent the most serious forms of illness and deaths,” says Portillo. Public health agencies are encouraging people, especially expecting parents, to get fully vaccinated and not to forget their boosters. In doing so, everyone can contribute to protecting themselves, those with underlying health conditions, and infants who are at particularly high risk but are too young to receive the vaccine.

Although current vaccines do well to mitigate severe disease, there is preliminary evidence suggesting that B. pertussis has undergone genetic changes and started a movement toward vaccine escape, which occurs when mutations in the pathogen render vaccines less effective. Clinical development programs are well underway to develop the next generation of pertussis vaccines to enhance protection and prevent transmission in new ways.

BlueDot will continue to monitor pertussis outbreaks and follow scientific innovation. To keep updated about whooping cough – or other outbreaks – you can sign up here to receive every edition of BlueDot Outbreak Insider.