H5N1 is circulating virtually unchecked in dairy cattle, increasing chances of a spillover into humans — and raising the threat of a pandemic

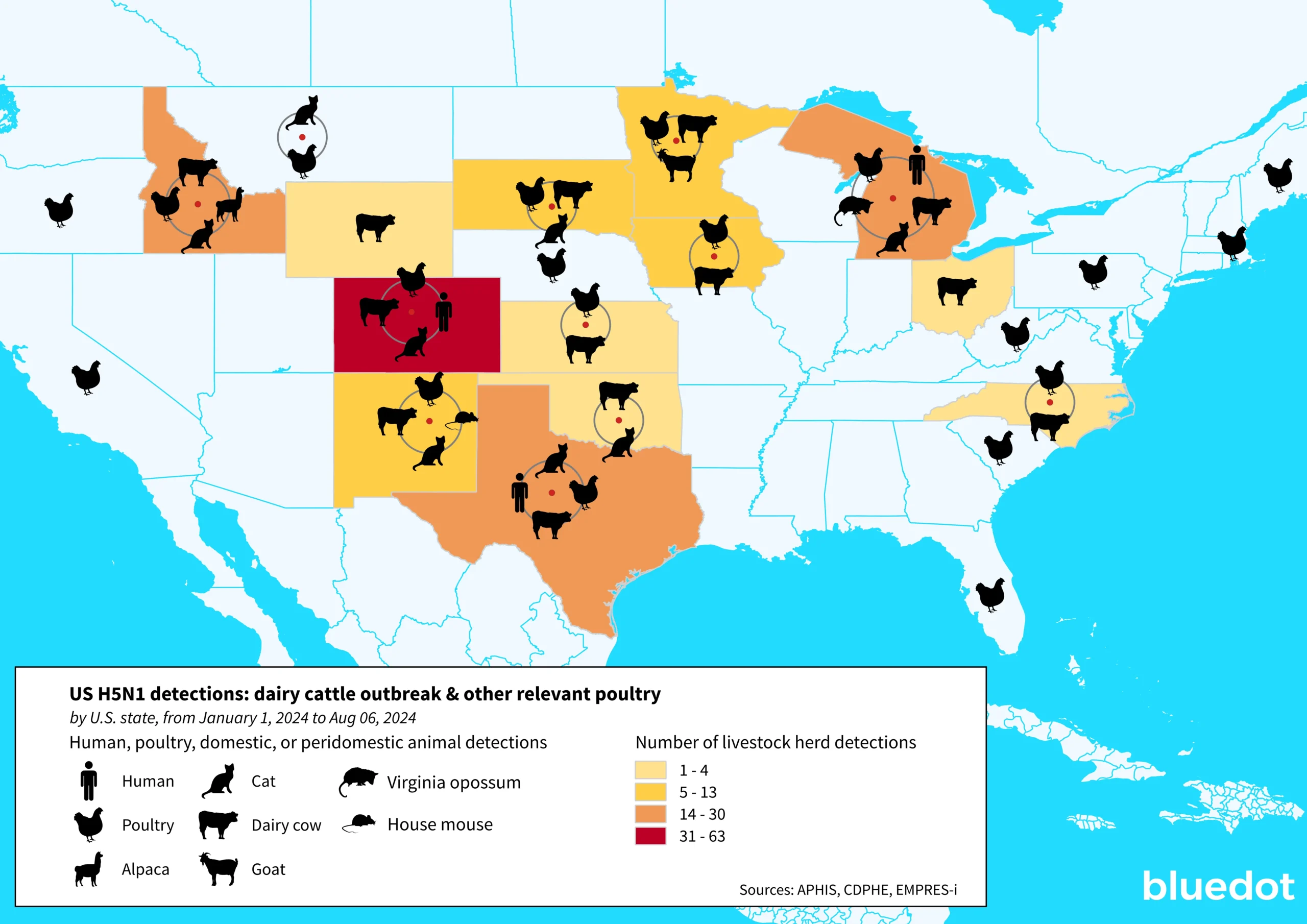

On February 8 of this year, the United States Department of Agriculture A(H5N1) declared an ongoing outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HAPI) A(H5N1) on commercial poultry farms. Since then, HPAI A(H5N1) – so called for its ability to cause severe illness among poultry species – has reached unprecedented levels on American farms. As of August 6, outbreaks have been recorded in 190 livestock herds across 13 states, and over 100 million poultry have been affected in almost every corner of the country. The US has also reported 13 human cases of avian influenza since April 1, 2024, the country’s largest-ever recorded outbreak and the largest globally this year. And while the risk to the general population is considered low at the moment, the virus continues to circulate and infect new animal species, raising the concern that it could become endemic in some animal populations and eventually better adapted to human hosts.

Outbreak Insider sat down with the experts on BlueDot’s Surveillance team to get an update on the current situation, from trends in avian influenza spread to current and future public health measures and their challenges — including the “tipping point” that scientists are closely watching for. BlueDot has continuously provided updates to its clients on the evolving situation, and one thing is certain: the time to prepare for avian influenza is now.

What is the current status of avian influenza? How has the situation changed in recent weeks?

For months now, case counts of H5N1 among dairy cattle and poultry have not wavered. In particular, the B3.13 genotype of HPAI A(H5N1) — the one that is circulating among dairy cattle — has demonstrated the ability to transmit efficiently between cows.

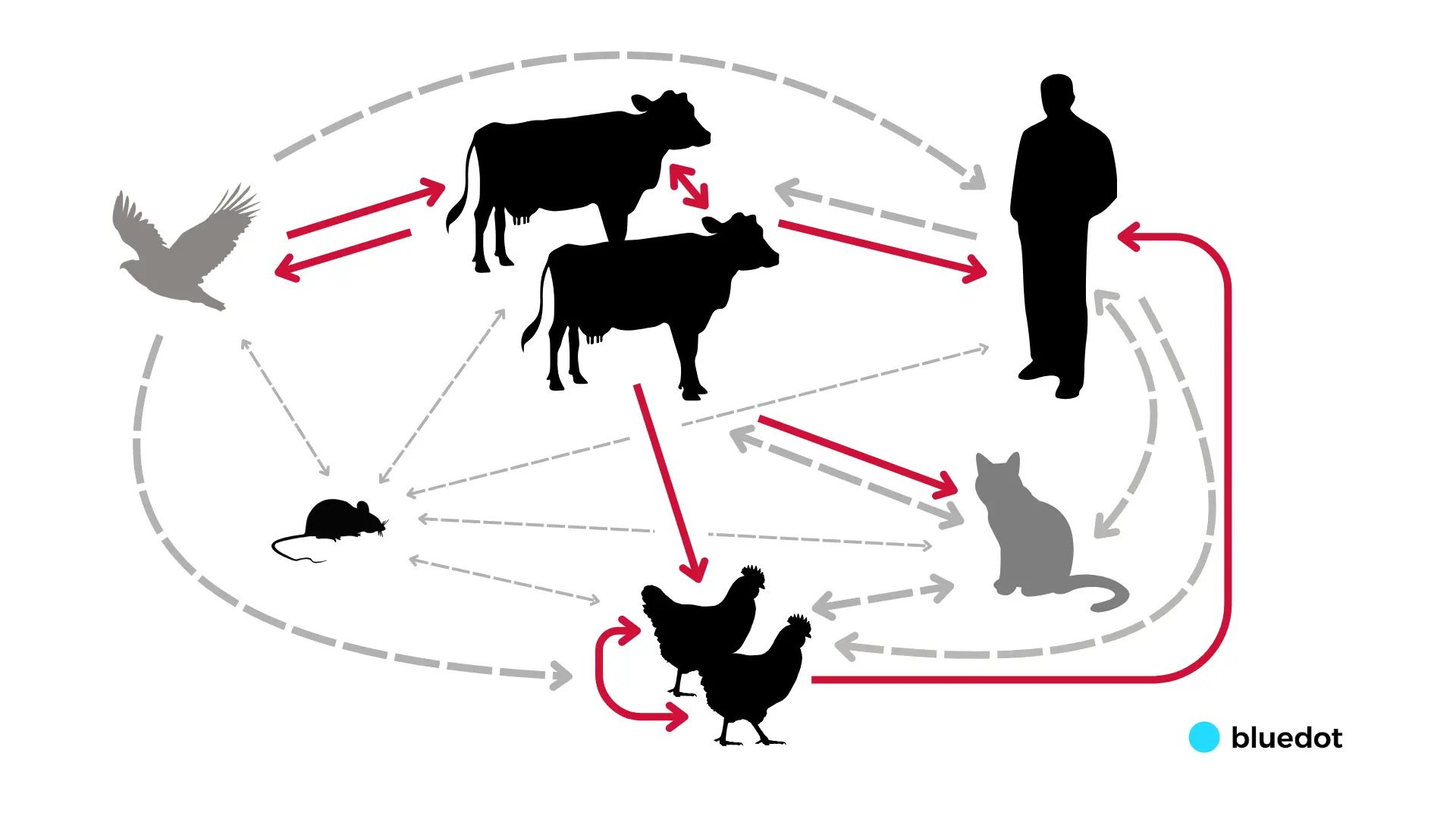

The virus also continues to spread among other proximal animal populations such as cats and mice, which may complicate efforts to contain outbreaks. And the more avian flu spreads, the greater the concern that it could become endemic in animals such as cows, making them a permanent reservoir for the virus and increasing the chances it could better adapt to humans.

Since April, four dairy and nine poultry workers have contracted avian flu. Experts believe this is an underestimate because of challenges with detection. Fortunately, these cases have been mild and can be connected to a clear exposure to environments or animals that were known to be infected with HPAI A(H5N1).

We haven’t seen human-to-human transmission or human infections in low-exposure or uncontaminated settings yet, which is why the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently considers the risk to the general population low. But how the virus is transmitted among newly affected agriculture settings is still not fully understood. We need an adapted strategy to minimize, contain, eliminate – and ideally, prevent – avian influenza outbreaks.

You say there are challenges in detecting cases. How reliable are the data we have?

Scientists are working incredibly hard to keep up with the spread of avian influenza, but it’s not easy. For one, detection of human cases in the US has mainly relied on self-reported symptoms and voluntary testing of symptomatic individuals, such as in Michigan where those on affected dairies were enrolled in a text-message-based system and were encouraged to report any compatible symptoms. Ultimately, almost all the cases in the US we know about have been in those who have come forward with symptoms following exposure to the virus, meaning it’s likely that some cases are going untracked.

To complicate things further, efforts to collect epidemiological data on H5N1 dairy cattle outbreaks have been hindered by fears of economic damage to dairy businesses and stigmatization of farm workers. As seen in Texas, many farm workers are migrants who may worry that illness will affect their ability to work and support their families. Closer collaboration with at-risk populations – especially farm workers – is paramount to prevent the worst-case scenario: the emergence of a pandemic strain.

Where do things stand in terms of H5N1 vaccine development and use?

Vaccines for avian influenza in humans do exist. Europe has three H5N1 vaccines available for use right now during outbreaks. The US also has three approved H5N1 vaccines, though none are for broad public use. The US did recently order an additional 4.8 million doses to bolster the national vaccine stockpile. But these vaccines are not new, and we do not know how effective they will be against emerging strains in practice until they are rolled out and studies are conducted. Like other vaccines for infectious diseases, the vaccines for H5N1 would likely need to be updated to target the specific strain causing an outbreak in humans – and this takes time.

That’s why public health agencies and pharmaceutical companies have ramped up investment in vaccine development. Just last week, the WHO launched a new project to develop H5N1 vaccine candidates for low-and middle-income countries. Last month, the US government awarded Moderna $176 million to develop an avian flu vaccine. And Pfizer also has a vaccine candidate under development.

These recently announced vaccine candidates will use mRNA technology, allowing for more rapid viral updates and manufacturing. This is important because if the virus does mutate into a pandemic strain, the need for vaccines will be acute. Should this happen soon, resources would likely be diverted from seasonal vaccine manufacturing to rapidly scale available doses.

In the meantime, how are public health agencies responding to the situation?

Public health measures in the US are currently focused on protecting farm workers, which makes sense given their increased risk of exposure. Public health agencies such as the US CDC are supporting the monitoring and testing of symptomatic farm workers. They are also recommending isolation and antiviral medication for those infected and their close contacts, while providing additional personal protective equipment (PPE) for anyone working directly with animals or in contaminated environments.

We are also seeing some notable adaptations in public health strategy globally. Finland recently became the first country to offer farm workers vaccinations against avian influenza, and other countries are thinking of following suit. And just last week, the US CDC announced it will mount a seasonal flu vaccination campaign for farm workers, part of a $10 million investment in new protective measures that also includes better access to PPE and healthcare services for this sector.

The US CDC announcement may seem counterintuitive as the seasonal flu vaccine does not protect against avian influenza. But influenza viruses are particularly good at mixing and matching. If the viruses co-infect a human host, they could swap gene segments with each other – known as a reassortment event, which has the potential to lead to the emergence of a pandemic strain. In 2009 a similar situation —the reassortment of avian, human, and swine influenza strains in pigs —led to that year’s swine flu pandemic. By inoculating against the seasonal flu, we can mitigate the risk of co-infection and reduce the likelihood of a reassortment event.

3 Top Takeaways

- The virus is still spreading. The current response to avian flu in dairy cattle has proven insufficient to control its spread. The US is reporting 13 human cases, its largest-ever recorded outbreak of H5N1 in humans.

- The upcoming flu season poses a compounding public health challenge. As the fall arrives, so too does the seasonal flu, increasing the risk for co-infection. This not only makes it more challenging to detect avian flu in humans but also provides grounds for mutation, reassortment, and the potential emergence of a pandemic influenza strain.

- BlueDot is on the alert for signs of sustained human-to-human transmission. That hasn’t happened yet, which is why the risk to the general population is considered low. If it does, the risk rating will rise.

The current consensus is that the risk to the general public is low. What would increase that risk? What should we be looking for?

To date, we are seeing animal-to-animal and animal-to-human spread, but the turning point for human health would be the emergence of related clusters of human cases or several cases of unknown origin outside of agriculture settings, pointing to more efficient human-to-human transmission. BlueDot is closely monitoring the situation by combining our infectious disease intelligence with an AI-powered surveillance engine. We are looking for signs of changes in disease outbreak dynamics that would indicate critical mutational changes and point to a more transmissible strain of avian influenza.

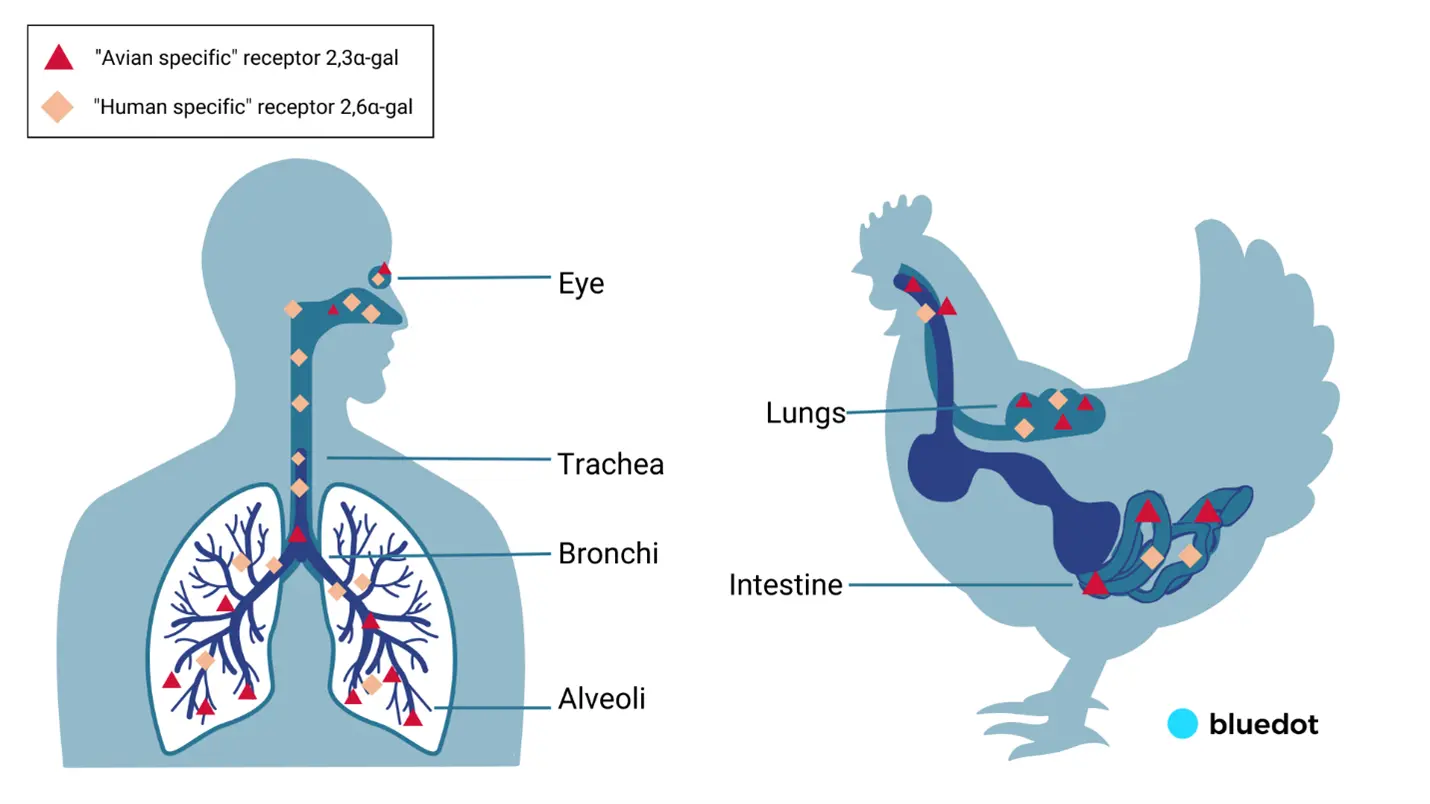

In order for a strain with pandemic potential in humans to emerge, the virus would need to change and adapt to allow for greater viral replication, increased binding to human-type receptors, increased pH and heat stability of the virus in the human upper respiratory tract, and viral evasion of human immune factors.

That said, the United Kingdom’s Health Security Agency (UKHSA), using a scale that runs from zero to six, raised its risk assessment for avian influenza A(H5N1) B3.13 genotype to level four due to sustained and multispecies mammalian outbreaks – a sign that the threat to human health is becoming increasingly more pressing.

You say there are challenges in detecting cases. How reliable are the data we have?

The tale of avian influenza is far from over as great uncertainty remains in how the virus is transmitted and its projected trajectory. The experts at BlueDot are dedicated to providing you with the latest updates before anyone else. To stay abreast of important changes in avian flu and beyond, subscribe to BlueDot’s newsletter, Outbreak Insider, here.