Mosquito and parasite adaptations are driving a marked increase in malaria cases — and hampering control efforts around the globe

After a decade of declining cases, malaria has suddenly taken flight.

The latest malaria report by the World Health Organization estimates that there were more than a quarter-billion cases and nearly 600,000 deaths globally in 2023 — an increase of 11% and 5%, respectively, from five years earlier, in 2019. Nearly all malaria cases were reported in Africa, and approximately 75% of deaths were in children under 5 years of age. The parasitic disease accounts for approximately 85% of 700,000 yearly vector-borne disease deaths.

“Malaria is why we say that the mosquito is the deadliest animal on the planet,” says Andrea Thomas, PhD, BlueDot’s head of epidemiology. Climate change is expanding the habitat for the mosquitoes that carry malaria. A malaria-carrying species from Asia has gained a lasting foothold in Africa. Mosquitoes have also become more resistant to insecticides, while malaria parasites have adapted to evade detection and resist key treatments.

Together, these factors have combined to present a significant new challenge for disease control. The groundbreaking development of an antiparasitic vaccine — a remarkable breakthrough, the culmination of 60 years of research — is a key weapon in the battle to contain malaria. Yet a global immunization effort, along with innovative disease control approaches, is needed to preserve the hard-won decades of progress that are currently at risk.

Mapping malaria

Malaria is a parasitic disease that has beset the earth since at least the time of the ancient Egyptians and ancient Greeks, afflicting both King Tut and Alexander the Great. It is caused by five different Plasmodium parasites, the deadliest of which is Plasmodium falciparum. The pathogen is transmitted by the Anopheles mosquito, which is found in tropical and subtropical regions around the world.

The parasitic disease differs from other mosquito-borne infections like dengue, chikungunya, or Zika, which are caused by viruses and are transmitted by the Aedes mosquito — a genus of species found in similar climates that tend to be active during the day. And while other arboviruses such as Zika, yellow fever, and West Nile typically confer lifelong immunity following an initial infection, a malaria infection does not, people can be repeatedly infected. The bite of an infected mosquito transmits parasites which travel to the liver, where they mature, and then infect and damage red blood cells. Symptoms often take 10-15 days to develop and are similar to other mosquito-borne diseases: fever, headache, and chills. These symptoms constitute uncomplicated malaria. For a considerable number of patients, however, malaria can lead to severe and chronic outcomes such as anemia, difficulty breathing, seizures, and death.

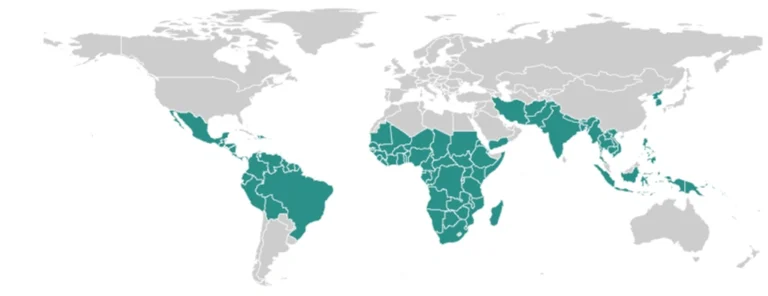

Malaria is a world-leading cause of preventable illness and death. In the 2024 WHO World Malaria Report, there were an estimated 263 million cases across 83 endemic countries in 2023. Africa accounted for roughly 94% of cases, with more than half of cases attributable to Nigeria (68.1 million), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (33.1 million), Uganda (12.6 million), Ethiopia (9.6 million), and Mozambique (9.3 million).

Malaria Endemic Countries in 2023

Source: 2024 WHO World Malaria Report.

Nearly 600,000 malaria-associated deaths were estimated in 2023. The vast majority (95%) of fatalities were reported in Africa, and nearly three-quarters of deaths were in children under 5. Children and pregnant women are particularly susceptible to severe infection, as are those with HIV/AIDS and travelers who lack immunity.

From 2005 to 2015, public health efforts gained significant ground as cases and deaths declined. But incidence stabilized in the years after 2015 before ticking up in 2023, with 11 million more cases than reported the year prior. Between 2015 and 2023, malaria incidence increased by 4.1% and mortality rate decreased by 8.1%. The decline in deaths may be partially attributable to the introduction of malaria vaccines, though it is too early to tell.

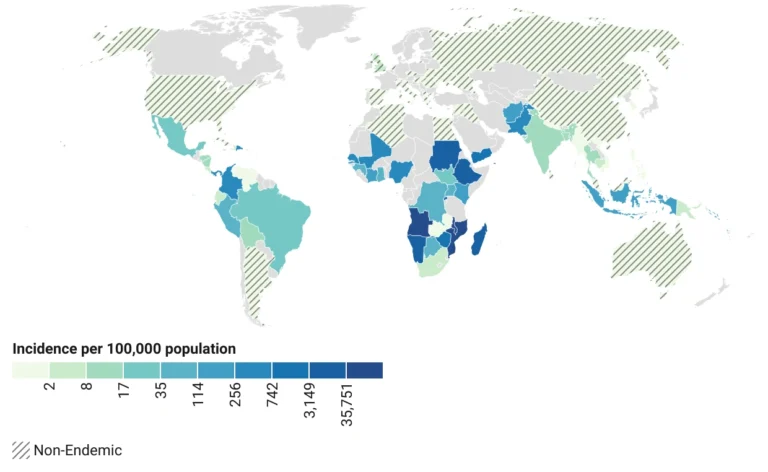

As of June 18, BlueDot’s global event-based surveillance system has recorded over 18 million cases and nearly 5,000 deaths so far this year. Nearly all (98%) of cases are localized to Malawi, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Angola, and Nigeria. These numbers are likely an underestimate due to reporting delays and country-specific surveillance capabilities. As extreme weather, humanitarian crises, and economic barriers threaten disease control, cases are projected to continue rising, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality.

Global Malaria Incidence, Jan 1, 2024-June 18, 2025

Source: BlueDot Human Cases and Deaths API; data collected June 18, 2025. Created with Datawrapper.

A clash for control

Between 2000 and 2023, 2.2 billion cases and 12.7 million deaths due to malaria were prevented around the globe. All told, 46 countries and one territory achieved malaria-free status, the most recent being Suriname in June 2025.

But like all vector-borne diseases, climate change is bringing warmer temperatures and variations in precipitation, creating ideal breeding grounds for mosquitoes to thrive. Model projections anticipate a 1.6-month longer transmission period and an additional 4.7 billion people at risk by 2070 as the malaria epidemic belt moves northward to include North America, central northern Europe, and northern Asia.

Malaria-carrying mosquitoes are already emerging in new areas and are re-emerging in areas they have not been for decades. The Anopheles stephensi, an adaptable, urban-dwelling mosquito from the Indian subcontinent that can transmit malaria year-round, has migrated and established itself in Africa — the region already hardest hit. With the ability to transmit the two most severe malaria parasites, An. stephensi’s arrival poses a massive threat to more densely populated areas across the continent. And a new species of Anopheles mosquito was recently discovered in Kenya and Tanzania, presenting yet another vehicle for malaria transmission.

Beyond expanded mosquito habitats and new vectors, both the disease and its carrier have improved their methods of avoiding prevention, detection, and treatment. Some mosquitoes, including An. Stephensi, have developed resistance to insecticides used in residual spraying and bed nets, which have long served as key vector control measures. Data from 2018-2023 showed that 57 of 66 endemic countries (86%) were experiencing resistance to at least one insecticide. More recently, insecticide resistance has been reported for all available types.

Malarial parasites are also evolving to evade detection. By deleting genes that encode proteins the most commonly used tests are looking for, the pathogen has become virtually undetectable, with false-negative test rates reaching as high as 80%. Evidence of gene deletion has been reported in 41 endemic countries across South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. The resulting under-detection can lead to more severe outcomes as cases go untreated.

While new tests are needed to improve detection, the parasites are also becoming more resistant to treatment. The most effective antimalarial medication, artemisinin, is taking longer to work and isn’t killing off all parasites like it used to. Drug resistance has been found in Eritrea, Rwanda, Uganda, and Tanzania, with yet more countries suspected. If the parasites that cause malaria continue developing drug resistance at the current rate, experts anticipate that about one-third of infections could be untreatable by 2030.

3 Top Takeaways

- Malaria makes a resurgence following a decade of decline. In 2023, there were an estimated 263 million malaria cases — an increase of 11 million from the year prior — and 597,000 associated deaths around the world, with Africa bearing the brunt of the burden. The changing tide in malaria trends comes after hard-won declines between 2005 and 2015.

- Mosquito and parasite adaptation muddy vector control efforts. New and existing disease vectors, along with detection avoidance and resistance to insecticides and treatment, mean the disease is becoming harder to track, control, and treat.

- Malaria response is lacking despite introduction of vaccines. The advent of an antiparasitic vaccine — a feat of vaccine development — offered hope in malaria containment. But global demand and distribution needs have not been met due to severe underfunding.

Mounting a global defense against malaria calls for sustained commitment

The malaria vaccine — the world’s first-ever antiparasitic vaccine, a scientific feat six decades in the making — became available in 2021. Within two years, a second vaccine was approved. Immunization against malaria has been shown to reduce uncomplicated malaria by 40%, severe malaria by 30%, and all-cause mortality by 13%.

The use of vaccines, and other disease control strategies, is especially important at a time when government funding is being cancelled in some places and questioned in others. This year, there was an estimated 36% cut in US Agency for International Development (USAID) funding for malaria programs. Global total malaria investment was already lacking, with less than half of the funding target met. If funding remains at this level, an additional 112 million cases and 280,000 deaths are expected between 2027 and 2029.

“Gaining control of malaria is like a balance scale,” says Thomas. “We are trying to tip the scale in the right direction with the vaccine.” With a new tool to combat malaria that was not available five years ago, the next step is for the global health community to mobilize for wider vaccine roll-out. This is vital for the more than 3 billion people at risk.

Malaria is a preventable and treatable disease, but decades of progress are on the line. Renewed approaches and sustained political and financial commitment to malaria prevention are paramount to avoid further disease expansion or the reintroduction and reestablishment of malaria, such as what was seen in Pakistan in 2022 following four years of no indigenous cases. As the vector and pathogen continue to reinforce their defense systems, so too should public health measures.

On our radar

- Chikungunya in France: As of June 24, eight locally acquired cases of chikungunya have been reported across six regions in France. An eight-fold increase from last year, these cases emerged earlier than in previous years, highlighting concerns for increased transmission risk. The nation has also recorded 645 imported cases since May, largely linked to outbreaks in the French islands of Réunion and Mayotte. Though not endemic, the mosquito vector is present, and increased chikungunya vigilance is needed.

- Dengue in Honduras: Approximately 7,500 cases of dengue have been reported in Honduras since mid-June, a 30% increase compared with the same period last year. The national spike in cases is occurring as the Latin American region reports a 70% decline in cases overall. With the rainy season underway, there is concern for more severe outbreaks and cases amid resource gaps to track and treat the virus.

- H5N1 in Cambodia: The Indo-Pacific country reported 6 human cases of H5N1 avian flu in the month of June, including 4 in less than one week. Since the start of 2025 Cambodia’s Ministry of Health has reported 11 human cases of avian influenza, including six deaths. All cases have thus far have been linked to direct exposure to infected poultry.

To keep up with mosquito-borne diseases — and all other infectious diseases — sign up here to receive every edition of BlueDot’s biweekly newsletter, Outbreak Insider.