Climate change is driving the global increase in tick-related illnesses, and lagging surveillance means their true burden is unknown

On a global scale, vector-borne diseases — that is, diseases carried and spread by invertebrates — represent more than 17% of infectious diseases and result in 700,000 deaths annually. Mosquitoes have long been the primary culprit of these illnesses, bringing severe infections like dengue and malaria to new regions of the globe as a warming climate expands their viable habitat. But there is another invertebrate that has been creeping into new corners of the world, albeit at a slower pace: ticks.

There are at least 27 known tick-borne diseases globally, including the well-known Lyme disease and the lesser known but potentially life-threatening Powassan virus. Yearly cases of these infections vary by disease and across geographic regions. But experts believe any estimates are largely underestimated due to limited surveillance.

“We don’t know the true burden of tick-borne diseases because we can’t find what we aren’t looking for,” says Dr. Mariana Torres Portillo, BlueDot’s head of surveillance. “But we do know that these diseases are emerging in places we haven’t seen them before.”

As climate change ushers in more suitable environments for ticks to thrive, tick-borne diseases are expected to continue to rise. With growing awareness of tick-borne diseases, and vaccine development in the works, the chronic burden of disease might be halted.

Tick-borne disease types and transmission

Ticks are small, crawling parasitic insects that latch onto animals and humans to hitch rides, sometimes enjoying their meal for a long while — and over long distances. Ticks cannot fly, nor can they jump (a common misconception). They wait on the edge of leaves or tall grass, a behavior known as “questing,” to attach to unsuspecting passers-by and begin feeding. In this way, they can both ingest pathogens from, and transfer them to, their hosts. There are numerous tick species, and they feed on a full buffet of hosts: mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians.

This makes ticks an effective vector for transmitting bacteria, viruses, and parasites. In fact, the majority of vector-borne diseases in temperate North America, Europe, and Asia are due to ticks, not mosquitoes. In the US, for example, ticks account for over 95% of vector-borne disease cases. There are several types of tick-borne diseases globally, including Lyme disease, tick-borne encephalitis (TBE), and Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHF). Ticks can carry more than one pathogen at a time; as a result, co-infections can occur in their hosts.

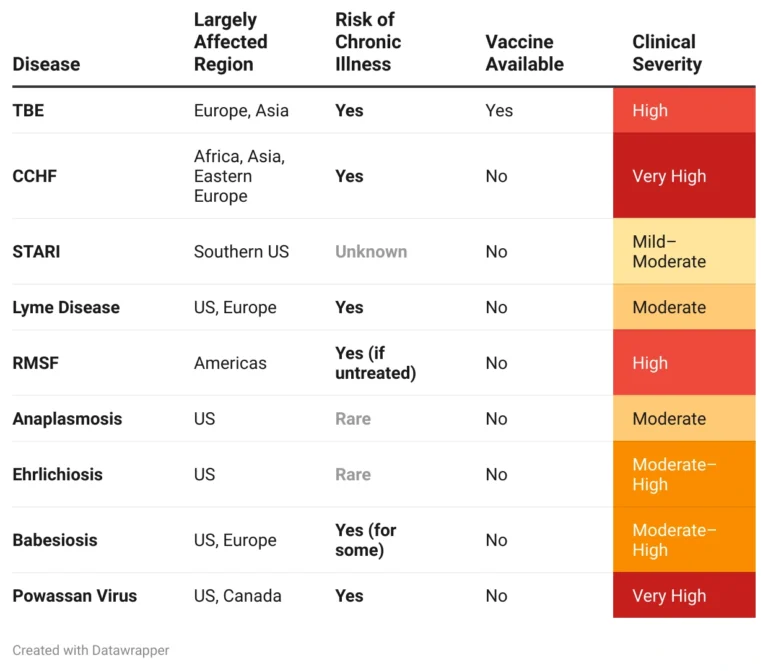

Common Tick-borne Diseases Around the World

Abbreviations: CCHF = Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever; RMSF = Rocky Mountain spotted fever; STARI = southern tick-associated rash illness; TBE = tick-borne encephalitis.

Source: BlueDot, June 13, 2025.

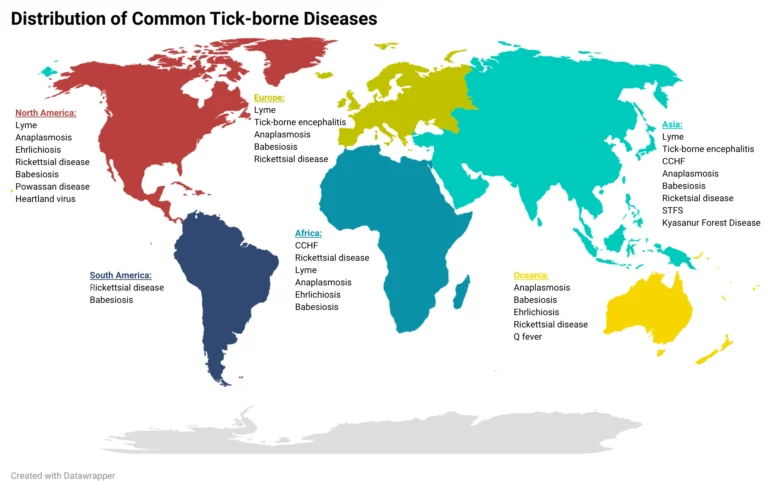

Creeping and crawling their way around the world

Ticks, and tick-borne diseases, have been reported around the globe. Ticks are commonly found in tall grass, wooded areas, and even leaf litter spanning rural, suburban, and urban areas; some species prefer moist environments while others like drier environments. Ticks thrive in warmer temperatures and are most active during spring, summer, and fall in temperate climates, and are often active year-round in tropical climates.

Global Distribution of Tick-borne Disease

Source: BlueDot, June 2025.

Over time, the prevalence of tick-borne diseases has increased. Climate change is a major driver, expanding the geographic range in which ticks can survive and extending the length of their active season. This gives ticks more time to grow and reproduce, increasing the number of ticks and lengthening the timeframe that hosts and ticks can interact. Host movement, bird migratory patterns, and habitat changes such as deforestation and reforestation also contribute to creating environments amenable to tick survival.

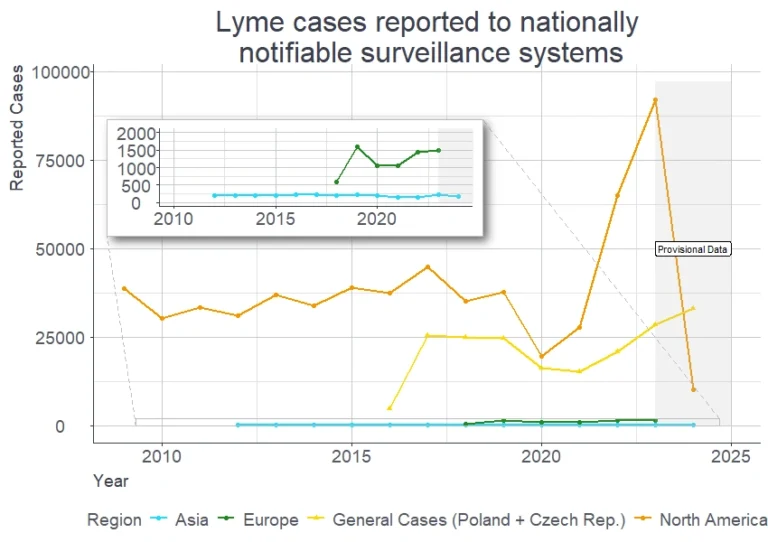

The most prevalent tick-borne disease is Lyme disease, caused by Borrelia bacteria, which has doubled in prevalence between 2010 and 2021. Endemic to North America, Europe, and Asia, BlueDot found that the top five countries with provisional/event-based data from 2024 were Poland, the US, Czech Republic, Lithuania, and Germany. But case counts are likely much higher as surveillance is hindered by a lack of detection, as well as by misdiagnosis, lack of mandatory reporting in many locations and delays in data aggregation. In fact, a 2022 meta-analysis reported that, in areas where Lyme disease is endemic, a substantial proportion of the population displays seropositivity markers that indicate previous Lyme disease infection.

Reported Cases of Lyme Disease, 2009-2024

Source: BlueDot, 2025. NOTE: Case definitions and surveillance levels may differ by reporting body. Notably, Poland and Czechia apply broader surveillance for Lyme disease. Data for 2024 is provisional and is likely an under-representation of true case burdens due to the lagging nature of tick-borne surveillance.

Among other tick-borne diseases, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) — endemic to the Balkans, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, — is a viral tick-borne infection affecting up to 15,000 people annually. Though not as prevalent as Lyme disease, it is more severe and is often fatal. The WHO has reported case fatality rates of up to 40% in CCHF outbreaks.

The lack of standardized and coordinated disease response, as well as limited awareness and resourcing in endemic regions, are major barriers to CCHF surveillance. Both CCHF and Lyme disease lack human vaccines.

Another common, and severe, viral tick-related infection that does have an available vaccine is tick-borne encephalitis (TBE). Up to 12,000 cases are reported annually across Europe, northern China, and Mongolia. As the name suggests, TBE affects the central nervous system and can result in meningitis and encephalitis. More than one-half of patients with TBE may experience long-term neurological sequalae or succumb to infection.

Evading detection

Just as tick bites can go unnoticed by their hosts, tick-borne disease often evades early detection. Symptoms of tick-borne diseases can emerge within days or weeks following a bite, depending on the type of disease. Often, these illnesses initially present with non-specific symptoms, such as a rash, aches, and fever, which make it challenging to diagnose. Meanwhile, the variable access, use, and interpretation of diagnostic tests for tick-borne diseases affects both accuracy for appropriate treatment, and renders trends for these diseases unclear.

The end result is that available data for tick-borne diseases lags, delaying awareness and prevention. Yet some diseases can result in more severe and chronic symptoms affecting the nervous system or the heart, especially when not treated during the early stages of infection.

3 Top Takeaways

- Tick-borne disease risk is heightened as climate change expands tick habitat. Milder winters and longer, warmer summers mean ticks can grow, reproduce, and survive longer in areas they’re active in — and break ground in new areas, too. In turn, tick-borne infections, like Lyme disease, are expected to rise.

- Cases of tick-borne disease are under-reported, and disease burden is underestimated. Tick-borne diseases can have long incubation periods and may be asymptomatic or present with mild symptoms, meaning people do not get diagnosed or treated — a state of affairs exacerbated by the lack of systematic surveillance globally.

- Tick-borne infection prevention is lacking. Despite growing awareness and progressing vaccine development, improved education, surveillance, and prevention measures are needed to combat tick-borne diseases globally.

A ticking time bomb

Climate change is expected to continue expanding tick populations and geographic spread — and tick-borne diseases are expected to continue rising around the world; indeed, new tick-borne pathogens continue to be discovered as geographic ranges expand. All told, tick-borne disease poses an ever-growing burden not just to public health, but to health care costs and the broader economy.

Tick-borne diseases have huge economic burdens. For example, Lyme disease was linked to 87% more outpatient visits and nearly $3,000 higher total healthcare costs per patient than controls in a one-year period. With an estimated 476,000 Americans diagnosed and treated for Lyme disease every year, the costs amount to up to $1.3 billion annually. Around one in four patients receive public support or disability benefits because of Lyme disease.

The impact of tick-borne diseases extends beyond humans, with approximately 80% of the global cattle population affected by tick-borne diseases, estimated to cost a whopping $13.9-18.7 billion USD. Together, the economic hit to agriculture and healthcare due to tick-related diseases is estimated at $30 billion USD in annual losses.

“Vaccines for tick-borne diseases are direly needed to reduce the impact on patients, the healthcare system, and society,” says Portillo. Vaccine candidates are in development for Lyme disease. The most advanced is the Phase 3 trial into a vaccine candidate produced by Pfizer and Valneva SE, which is anticipated to be put forward for regulatory approval in the US and European Union next year. The availability of this key preventive measure would be a massive step forward in mitigating infection and poor health outcomes.

Until then, greater clinical and public awareness and strengthened surveillance that includes the public in local data collection can help with earlier identification of tick bites, more accurate diagnosis, and rapid treatment initiation.

On our radar

- Mayaro virus disease in Brazil: From January to May 2025, 11 cases of Mayaro fever have been confirmed in Acre, Brazil, marking a 175% increase compared to last year. Similar to — and often misdiagnosed as — dengue and chikungunya, Mayaro virus is a mosquito-borne infection that presents with fever, rash, and joint pain. The risk of further expansion and larger outbreaks may increase, but local and national health authorities are enhancing surveillance, vector control efforts, and public education campaigns.

- Typhoid in the UK: Record high cases of travel-associated enteric fever (typhoid and paratyphoid fever) have been reported in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, with 702 cases based on provisional data from 2024. An 8% increase from 2023, the majority of cases have been linked to international travel to areas with poor sanitation and hygiene. With growing concern of drug-resistant typhoid strains and no licensed vaccine for paratyphoid, international collaboration is needed to track cases and mitigate treatment challenges.

- Mpox in Ghana: As of June 9, six new cases were confirmed, bringing the total confirmed cases to 85. The surge in mpox cases is associated with bolstered surveillance and contact tracing across the nation. The virus remains a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, and the risk of cross-border spillover from Sierra Leone amidst an explosive outbreak might lead to more expansive spread across the continent

To keep up with tick-borne diseases — and all other infectious diseases — sign up here to receive every edition of BlueDot’s biweekly newsletter, Outbreak Insider.