While dengue dominates the summer headlines, a rarely-noticed and poorly-understood disease — Oropouche fever — is spreading in record numbers

If you live in North America, Europe, Africa or Asia, you have likely never heard of Oropouche. Even among those working in the public health or infectious disease fields, the virus is largely unfamiliar. Pronounced o-ro-PU-chay, it is a vector-borne pathogen spread by small biting flies called midges and native to the tropical regions of Latin America, causing a broad range of symptoms in humans. And it’s currently spreading more widely than ever before, with five different countries now reporting substantial outbreaks.

All of which makes Oropouche fever an ideal topic for this inaugural edition of BlueDot Outbreak Insider, our new disease surveillance newsletter. You can sign up here to receive every edition of BlueDot Outbreak Insider, which will provide you with a snapshot of BlueDot’s latest industry-leading outbreak intelligence at regular intervals throughout the year.

Oropouche 101: What it is and how it spreads

The Oropouche virus is an arbovirus named for the region of the Caribbean nation of Trinidad and Tobago where it was first identified in 1955. And while there have been occasional Oropouche fever outbreaks of note in the intervening 69 years, the world has never seen anything like the virus’ recent activity.

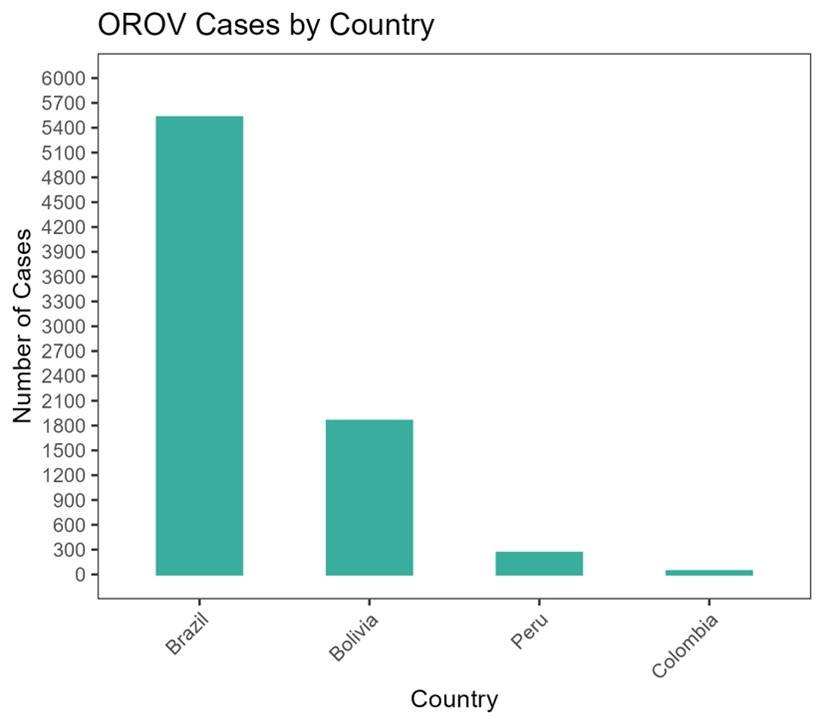

Oropouche fever outbreaks have now been reported in five countries: Brazil, Bolivia, Columbia, Peru and most recently Cuba. It’s the first time so many countries have simultaneously reported Oropouche fever cases — and the first time ever for Cuba, evidence that the virus’ geographical footprint is expanding.

That footprint could get bigger still: the disease’s principal vector is the Culicoides paraensis midge, whose presence has been detected from the northern United States down to southern Argentina. As the map below shows, the vast majority of Latin American countries are familiar with C. paraensis, and most of those have reported Oropouche fever outbreaks in the past.

The Oropouche virus causes symptoms in humans that include acute fever and muscle pains lasting from 2 to 5 days. More than half of Oropouche fever cases also can present with symptoms such as dizziness, light sensitivity (known clinically as photophobia) and joint pain.

4 Top Takeaways on Oropouche

1. It’s spreading like never before. For the first time ever, five countries — Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, and Cuba — have reported recent and or/active Oropouche virus outbreaks. In Cuba’s case, it’s the country’s first-ever outbreak of the disease — which indicates it’s now spreading farther afield than usual.

2. It’s vector-borne. While outbreaks are currently limited to tropical regions, the range of Oropouche’s primary vector, the C. paraensis midge, reaches from southernmost Argentina to the Great Lakes region of North America.

3. Its symptoms are mild but can be persistent. There have been no recorded fatalities due to Oropouche virus, but the disease’s symptoms (fever, muscle aches) can recur 2 to 3 weeks following initial recovery and in some other cases can lead to neurological complications such as meningitis.

4. It’s easily mistaken for dengue. Both Oropouche and dengue fevers are caused by arboviruses with initial symptoms that can overlap, but whose epidemiologies are decidedly different, underscoring the need for broader testing and deeper research.

Those symptoms are similar to other vector-borne viruses such as malaria, chikungunya, Zika and most notably dengue, which has been top-of-mind among infectious disease and public health officials due to the unprecedented global scale of its outbreaks this year. Indeed, if Oropouche fever is not tested for, it can be easily mistaken for dengue — and testing capacity for Oropouche is currently not widespread, even in the countries now reporting outbreaks, which leads BlueDot to believe that the Oropouche virus is currently under-detected.

“It’s important for front-line physicians and public health officials to know that, when they are confronted with these symptoms, they cannot assume it’s all dengue,” says BlueDot’s head of surveillance, Dr. Mariana Torres Portillo. “There are aspects of Oropouche virus that make it a distinct infectious disease threat all on its own.”

The virus's “known unknowns”

Though the Oropouche virus’ existence has been documented for well over half a century, it is not as well understood as other arboviruses or infectious diseases. There has yet to be a recorded instance of Oropouche transmission between humans, or from other animals to humans — but it’s unclear which animals serve as reservoirs for the virus. Research has identified several species of monkeys, as well as sloths and birds, as potential contributors to the sylvatic cycle of transmission.

Oropouche fever’s epidemiology is further complicated by multiple strains of the virus. A recent research study from Brazil has documented a likely new lineage responsible for recent upward trends and that could be the result of reassortment of the virus’s genome, which can be a frequent phenomenon for the Oropouche virus. “This combination of factors — upward trends, new lineage of the virus, and geographic expansion — is highly indicative that the virus is changing,” says Portillo. “That’s why we need to be monitoring it more closely.”

Its effects on the human body can also be surprisingly persistent. While there has never been a recorded fatality caused by an Oropouche infection, its symptoms often recur some 2 to 3 weeks after initial recovery, for reasons that are still poorly understood. And some cases have resulted in hemorrhagic symptoms and neurological complications, which is of particular concern to public health.

“In recent years, there have been cases of meningitis in Latin America (Guatemala more recently), for which the underlying cause was never conclusively determined,” says Dr. Portillo. “It’s entirely possible that the Oropouche virus was the initial infection that led to meningitis.” As testing for the Oropouche virus becomes more widespread, public health officials will be able to gather more accurate data on the scope of the disease and its prevalence in affected regions.

Taking action on Oropouche

There is currently no vaccine to protect against the Oropouche virus, and arboviruses can present unique challenges to the development of effective vaccines. Given the genetic diversity of the virus and the requirement for a vaccine that offers extensive protection against various strains, formulating a vaccine presents a significant challenge. That said, several vaccines are in development or have been tested in clinical trials, which provides a promising basis for the future prevention of Oropouche fever.

Due to the expansion of the epidemic range and the segmented nature of the genome, the likelihood of OROV genome reassortment events has likely increased. This phenomenon is more commonly observed in Bunyaviruses and, in certain cases, is associated with a rapid increase in disease severity.

It’s worth noting that public health officials have yet to record an imported case of the disease in a non-endemic country. Given its rising case numbers, it’s likely just a matter of time. And given that the presence of C. paraensis has been reported as far north as Wisconsin, public health officials would be wise to prepare for the possibility of infections in their own jurisdictions. That includes ramping up testing capacity and educating both front-line healthcare workers, and the general public, about Oropouche’s probable spread, symptoms and course of disease.

One final fact about the Oropouche virus to keep in mind when it comes to the potential for imported cases: humans are not a dead-end host. Infected people can transmit the virus back to the C. paraensis midge and to other species of mosquito, raising the possibility that the virus could spread in non-endemic regions through other vector species — and further underscoring the need for increased testing capacity.

“Dengue has been front-of-mind for public health officials around the world, and for very good reason,” says Portillo. “But the risk is that we end up underestimating and under-reporting other pathogens such as Zika, chikungunya and now the Oropouche virus. We need to be on the alert for all of them.”

Don’t miss the latest outbreak intelligence from BlueDot.

Sign up here to receive every edition of our BlueDot Outbreak Insider newsletter.