Watch the Uncovering mpox: The underestimated crisis and its international spread webinar to learn more.

New strains, surging cases, and spread to new regions make the latest mpox outbreak in Africa an international public health threat

On August 14 the World Health Organization (WHO) declared mpox a “public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC),” following the first-ever emergency declaration made by the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) a day prior. This is the second time the WHO has made the PHEIC declaration for mpox in the last two years, which is unprecedented. This year’s case counts already outnumber those from 2023.

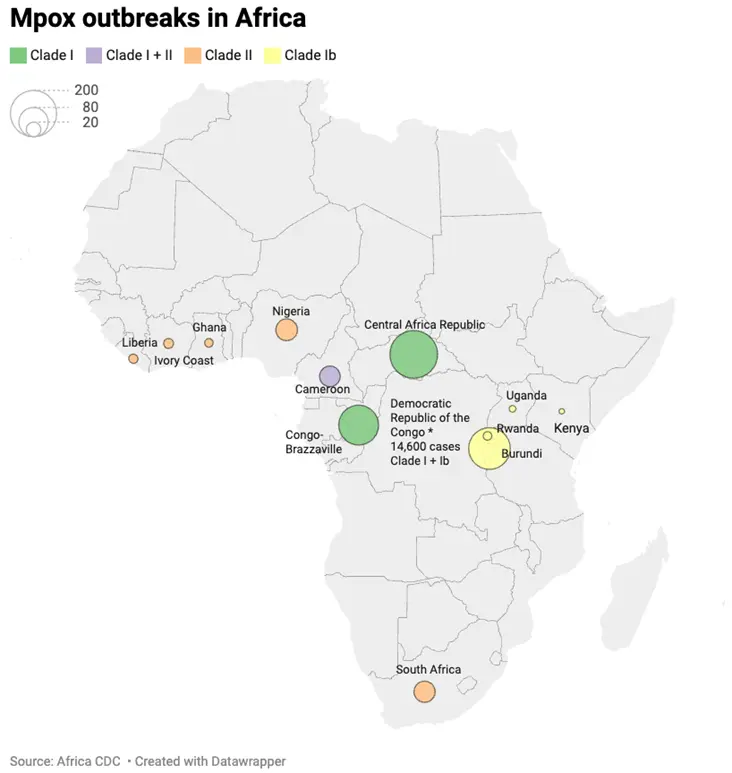

Since the beginning of 2024, more than 15,000 cases and 500 deaths have been reported across Africa. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is the epicenter of the outbreak, where approximately 14,000 cases have been reported so far this year. Notably, more than 70% of cases and 85% of deaths are among children 15 years and under. As cases increase in endemic countries such as the Central African Republic and the Republic of the Congo, others — namely Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda — are now reporting mpox cases for the very first time, raising concerns about continued geographic spread.

The mpox outbreak is marked by yet another concern: the emergence of a new strain, clade Ib. A subtype of clade I – considered to be the more severe of the two mpox clades – clade Ib is currently spreading rapidly and is also harder to detect on tests specifically designed to identify mpox clade I. As such, this may mean that there are many cases of a potentially more severe and transmissible mpox strain circulating undetected.

“The challenges with surveillance and testing in the region means the scale of the threat is likely underestimated,” says Andrea Thomas, PhD, BlueDot’s Head of Epidemiology. “The lack of resources including vaccines, ongoing conflicts, and many unknowns make responding effectively incredibly difficult.” BlueDot has been monitoring mpox in the DRC for quite some time, releasing six outbreak alerts since November last year with Intelligence Reports published in May and another just last week. In a region where public health resources are limited, there is a global call to action to contain the outbreak and bolster countermeasures in Africa — and around the globe.

What we know about mpox

An orthopoxvirus in the same family as smallpox, mpox (previously known as monkeypox) was first discovered in the late 1950s among monkeys being used for research. By 1970, the first human case was reported in the DRC. Vertebrates serve as natural hosts to the virus, which can spread to humans zoonotically through direct contact with infected animals, including monkeys, prairie dogs, and squirrels. Human-to-human transmission also occurs through direct contact, indirect contact, respiratory droplets or short-range aerosols from prolonged close contact.

Mpox infection presents in various ways, with symptoms that include a rash on the face, hands, feet, or genitals that can last up to a month. The rash is often accompanied by flu-like symptoms, including fever, headache, and muscle aches. In some instances, mpox can lead to severe illness and death, often resulting from complications such as pneumonia, encephalitis, or myocarditis. Newborns, children, those who are pregnant, and people with immune deficiencies are at increased risk. Notably, symptoms can take up to three weeks to present and research has shown that infected individuals can transmit the disease prior to symptom onset, which can make the spread of mpox more difficult to control.

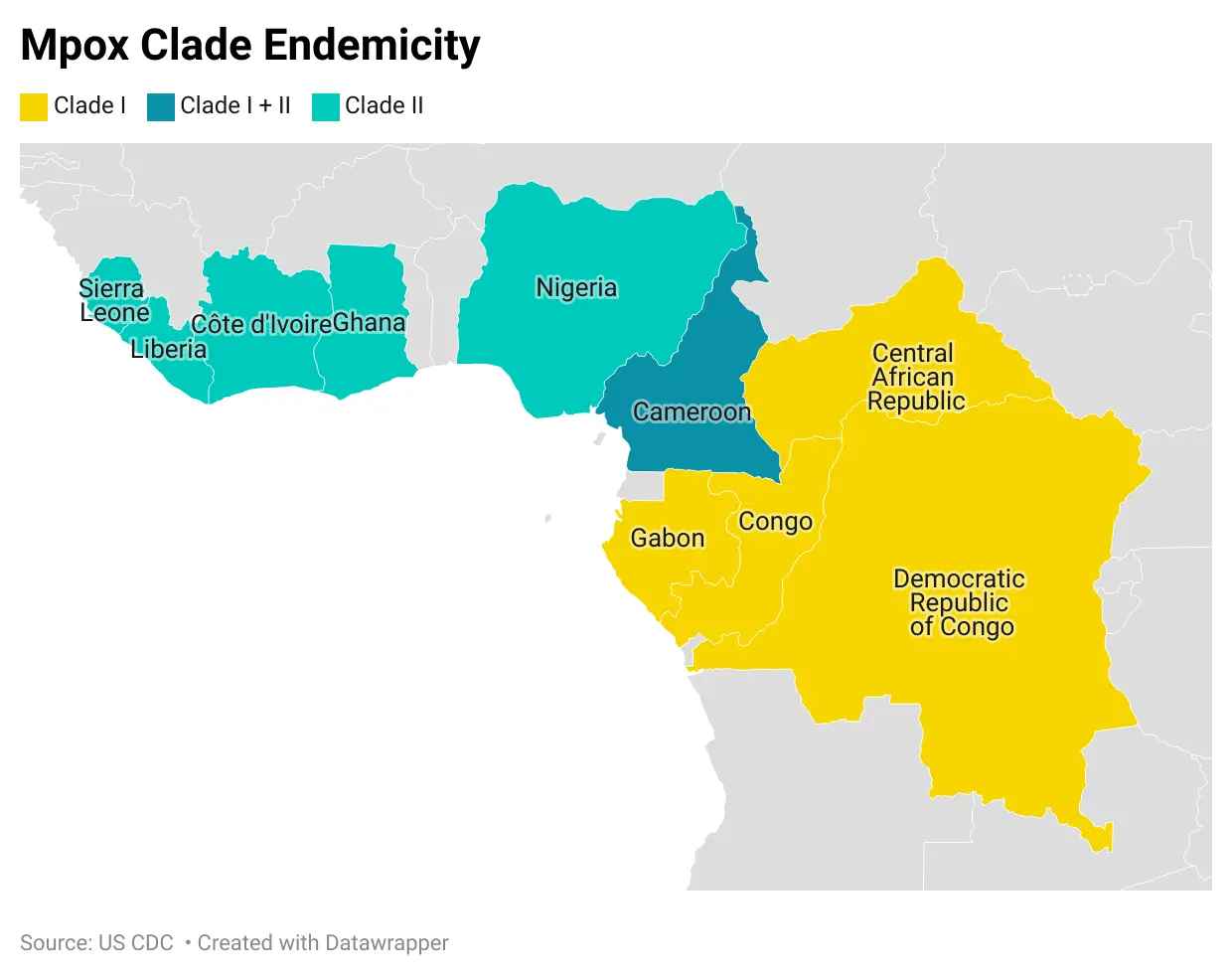

There are two types of mpox, clade I and II, both of which can be transmitted in any of the abovementioned ways. Clade II is thought to be less severe and was responsible for the 2022 outbreak, which primarily spread through sexual contact among highly connected communities of men who have sex with men. Clade I carry a higher case fatality rate in the region where it is endemic, and it may be more easily transmissible than it had been previously. It is the type of mpox primarily responsible for the current outbreak, in part due to clade Ib’s transmission among adults via sexual contact in mobile heterosexual networks. Today, clade I is endemic to nations in central Africa while clade II is endemic to western Africa.

Globally, nearly 100,000 cases of mpox have been reported since the beginning of 2022. The vast majority of cases have been in Africa but the risk of imported cases is a rising concern. So far, Sweden and Thailand, have reported an imported case of Clade I mpox in the past week. The European Centres for Disease Prevention and Control raised its risk assessment for the disease, stating it is highly likely Europe will see more imported cases.

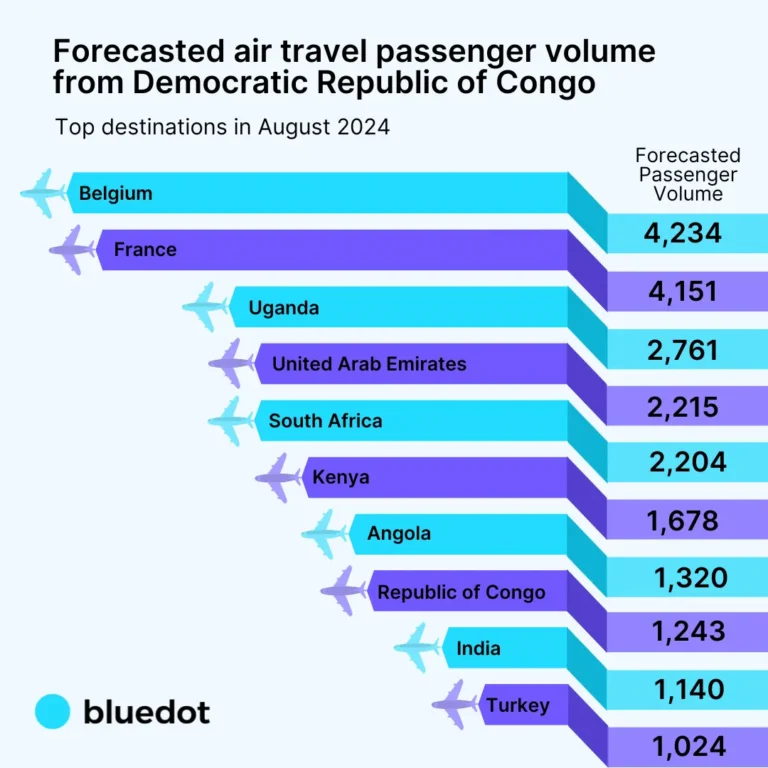

Based upon forecasted air passenger volumes travelling from the DRC, Belgium, France and Uganda are most likely to receive infected returning travellers in August 2024. Public health officials in Europe, where access to vaccines and healthcare are less of a barrier, are confident they can stop the spread of the disease, provided cases are detected early.

4 Top Takeaways

- Mpox is on the move as case counts surpass last year’s total. With cases of mpox surging in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and other endemic countries in Africa, the virus has spread to previously unaffected regions nearby and beyond the continent.

- Mpox has mutated, giving rise to a novel strain. Clade Ib, a subtype of the more virulent mpox clade I, has emerged. Not only is it spreading more easily between humans, it is also less detectable on tests.

- Mpox presents a public health predicament. With many known unknowns, including the transmissibility of the new clade and whether countermeasures will be effective, experts are facing immense challenges in mobilizing an effective response.

- Support is critical. Declared a “public health emergency of international concern,” there is a global call to action to support Africa’s efforts to contain mpox amidst concurrent outbreaks and a lack of resources.

Minimizing mpox’s public health threat

Public health experts in the DRC are battling to contain the mpox outbreak with limited resources while confronting many known uncertainties about the virus. For one, case counts and case fatality rates may be inaccurate as the virus goes underdetected due to lack of surveillance and testing capacities. This is further complicated by persistent stigma associated with mpox infection and since mpox is self-limiting – meaning it often clears up on its own – people may not come forward to seek testing and treatment.

Beyond challenges with surveillance, there are substantial gaps in the availability, accessibility, and effectiveness of current medical countermeasures. A recent randomized controlled trial found that the antiviral drug tecovirimat was not effective against lesions in clade I patients. More concerning is the lack of available vaccines to protect those most at risk, with estimates of only 50,000 vaccine doses in the DRC for a population of 99 million.

Despite long-simmering outbreaks of mpox on the African continent, the international community has yet to establish a program for accelerated mpox vaccine manufacturing and distribution in the most affected region. Of the available vaccines, the region faces considerable difficulties distributing them amidst several ongoing infectious disease outbreaks, including measles, meningitis, cholera, poliomyelitis, and malaria. Denmark-based Bavarian Nordic, one of few firms with an mpox vaccine, recently told the Africa CDC that it could supply up to 2 million doses this year and 8 million more by the end of 2025. The company is also looking at manufacturing the vaccine in Africa to expand its current capacity.

Despite determining that clade Ib seems better adapted to human-to-human transmission and is evading tests, many uncertainties remain. How easily the new clade spreads, how virulent it is, and whether the current vaccines can protect against it are yet-unanswered questions plaguing public health experts. Nevertheless, the focus now is on containing the outbreak before it becomes an epidemic across different regions worldwide.

“We need to work as a global health community and act where outbreaks are occurring,” says Thomas. To bolster the response to this public health emergency, the WHO has released US$1.45 million but anticipates needing US$15 million. With an outbreak of this magnitude and level of concern, public health agencies and organizations around the world are encouraged to support in the efforts to minimize the virus’s impact.

BlueDot has kicked into high gear in response to the mpox outbreak. The dedicated surveillance team is monitoring this rapidly changing situation to promptly share data and information about the virus’s spread. To keep updated on the mpox public health emergency, and other infectious disease outbreaks, sign up here to receive every edition of BlueDot Outbreak Insider. If you would like to receive a daily brief on mpox activity, please get in touch with us here.