Given its potential for harm, the current gaps in awareness, detection, and prevention of Lassa fever underscore the need for vaccines and treatment

Two weeks ago, the Iowa Department of Health and Human Services reported a fatal case of Lassa fever in a patient who had recently returned from West Africa. This marked the ninth known imported case of Lassa fever in the US in the last 55 years, the last of which was in 2015.

The rarity of Lassa fever is, paradoxically, precisely the reason why it is notable: it is a potential harbinger of undetected cases and larger outbreaks abroad, which is concerning for a disease labeled by the World Health Organization as having “pandemic potential,” and by the US Centers for Disease Control as a potential security concern.

Exported cases of Lassa fever to non-endemic regions, such as North America and Europe, are rare. For example, France saw its first imported confirmed case of Lassa fever in May 2024. England saw just two exported cases in 2009 and three in 2022. All told, between 1969 and 2019, only 36 cases of imported Lassa fever were identified around the globe. This is in sharp contrast to the estimated 100,000 to 300,000 cases and 5,000 deaths reported annually across nations in West Africa, where it is both endemic and consistently underestimated.

“Lassa fever is underreported,” says BlueDot medical science liaison Dr. Hernán Acosta. “When we see exported cases, it means there are many more that we are unaware of.” The risk of Lassa fever spreading to nearby countries is high. And amid significant outbreaks of other infectious diseases, such as malaria and mpox, Lassa fever often goes undetected and unprioritized. With so many gaps in understanding and managing Lassa fever, it is a looming global public health concern in need of greater attention.

The lowdown on Lassa fever

Like Ebola and Marburg (covered in a recent Outbreak Insider), Lassa fever is a zoonotic viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF). The disease, which was first identified in 1969 in the Nigerian town of Lassa, is caused by the Lassa mammarenavirus (LASV). The reservoir responsible for transmission is the Mastomys natalensis rodent, commonly called the African rat (though it is actually a species of mouse), native to sub-Saharan Africa. Most often, the main exposure risk is direct contact with contaminated food or household items. Rarely, human-to-human transmission can occur through bodily fluids.

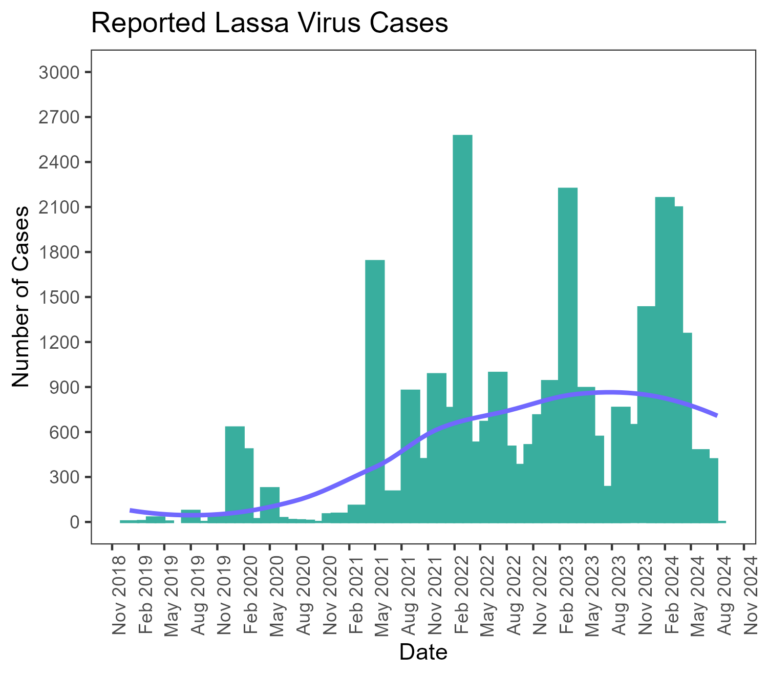

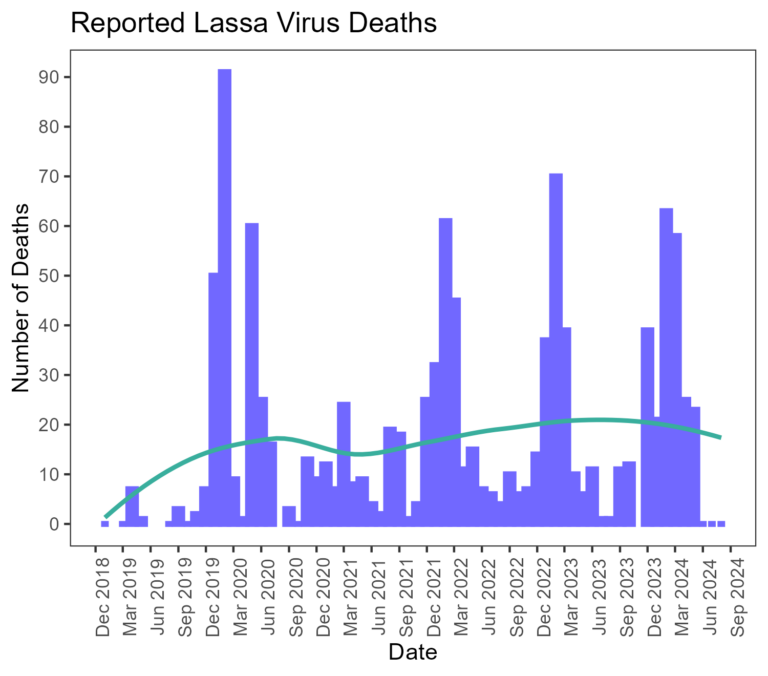

Lassa fever is endemic across most countries in West Africa, including Nigeria, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, where Mastomys natalensis resides. Between January 2019 and August 2024, 31,000 cases and 1,060 deaths were reported in endemic nations. Most of these cases were reported in Nigeria, which may be due to that country’s relatively stronger surveillance and testing measures. Cases of Lassa fever increase seasonally, with higher incidence during the dry season — from November to April — as rodents move indoors in search of food. Individuals living in rural locations where the reservoir is found, especially areas with poor sanitation or overcrowding, are at an increased risk for the disease. Healthcare workers who care for patients with Lassa fever are also at an increased risk due to challenges with infection prevention and control measures appropriate for this infectious disease.

Cases and deaths in endemic countries, January 2019 to August 2024

Source: BlueDot Biosecurity Series Report, Issue 3. October 30, 2024.

The incubation period is 2-21 days, though the virus can be detected in urine for up to nine weeks and in semen for up to three months after symptoms appear. Approximately 80% of cases are asymptomatic or experience mild symptoms, including fever, malaise, and sore throat, and the overall case fatality rate is approximately 1% in affected populations.

But for a significant proportion of cases, the consequences are more dire. One-third of those with Lassa fever experience hearing loss, which may be permanent. In about 20% of cases, the virus leads to severe organ damage. Some patients may experience severe neurological and hematological symptoms, such as convulsions, encephalopathy and internal bleeding. For patients who are hospitalized with Lassa fever, the case-fatality rate rises to 15%. Risk of death is especially high in late pregnancy, with maternal mortality and fetal loss in over 80% of cases in the third trimester.

Diagnosis is challenging due to varied and non-specific symptoms that often overlap with other infectious diseases, including Ebola, malaria, and yellow fever. There are no medical countermeasures specific to Lassa fever, so treatment involves supportive care and ribavirin — a non-targeted antiviral that lacks robust evidence supporting its use.

4 Top Takeaways

- Lassa fever (LF) flies under the radar. Despite regular outbreaks of LF in endemic nations in West Africa, with estimates of up to 300,000 cases and 5,000 deaths annually, LF often goes underreported amid co-occurring infectious diseases such as malaria. And though rare, travel-related cases like the recent fatal case in Iowa mean many more cases are likely circulating undetected.

- Lassa fever has pandemic potential — and the risk is growing. Climate and environmental factors, along with limited surveillance and healthcare capacity, are associated with increased spread. Up to 700 million people may be at risk, presenting substantial population health and economic burden.

- Lassa fever lacks available countermeasures. To date, no vaccine exists and the management of LF involves the use of non-specific treatments. Several vaccines and therapeutics are being studied, but these trials are affected by gaps in funding and logistical challenges.

- Lassa fever is a biosecurity concern. Due to a lack of available countermeasures and the ability of the virus to be aerosolized, LF has been identified by major public health organizations as a potential bioterrorism agent urgently needing greater research and development.

- Lassa fever (LF) flies under the radar. Despite regular outbreaks of LF in endemic nations in West Africa, with estimates of up to 300,000 cases and 5,000 deaths annually, LF often goes underreported amid co-occurring infectious diseases such as malaria. And though rare, travel-related cases like the recent fatal case in Iowa mean many more cases are likely circulating undetected.

Lassa fever’s risks: pandemic potential and weaponization

Lassa fever poses serious public health concerns in West Africa as the region faces concurrent outbreaks and limited resources. The true disease burden is likely much higher than reported due to a lack of sufficient surveillance and diagnostics in most countries. And with climate change, human activity, urbanization, and poverty threatening to facilitate the increased spread of Lassa fever, concerns are mounting as up to 700 million people may be at risk of infection. New research, modeling the next 10 years of Lassa fever in endemic countries, predicts 27 million cases, 237,000 hospitalizations, 2 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), and over 39,000 deaths in the absence of a vaccine. This amounted to a projected $1.6 billion in total cumulative societal costs.

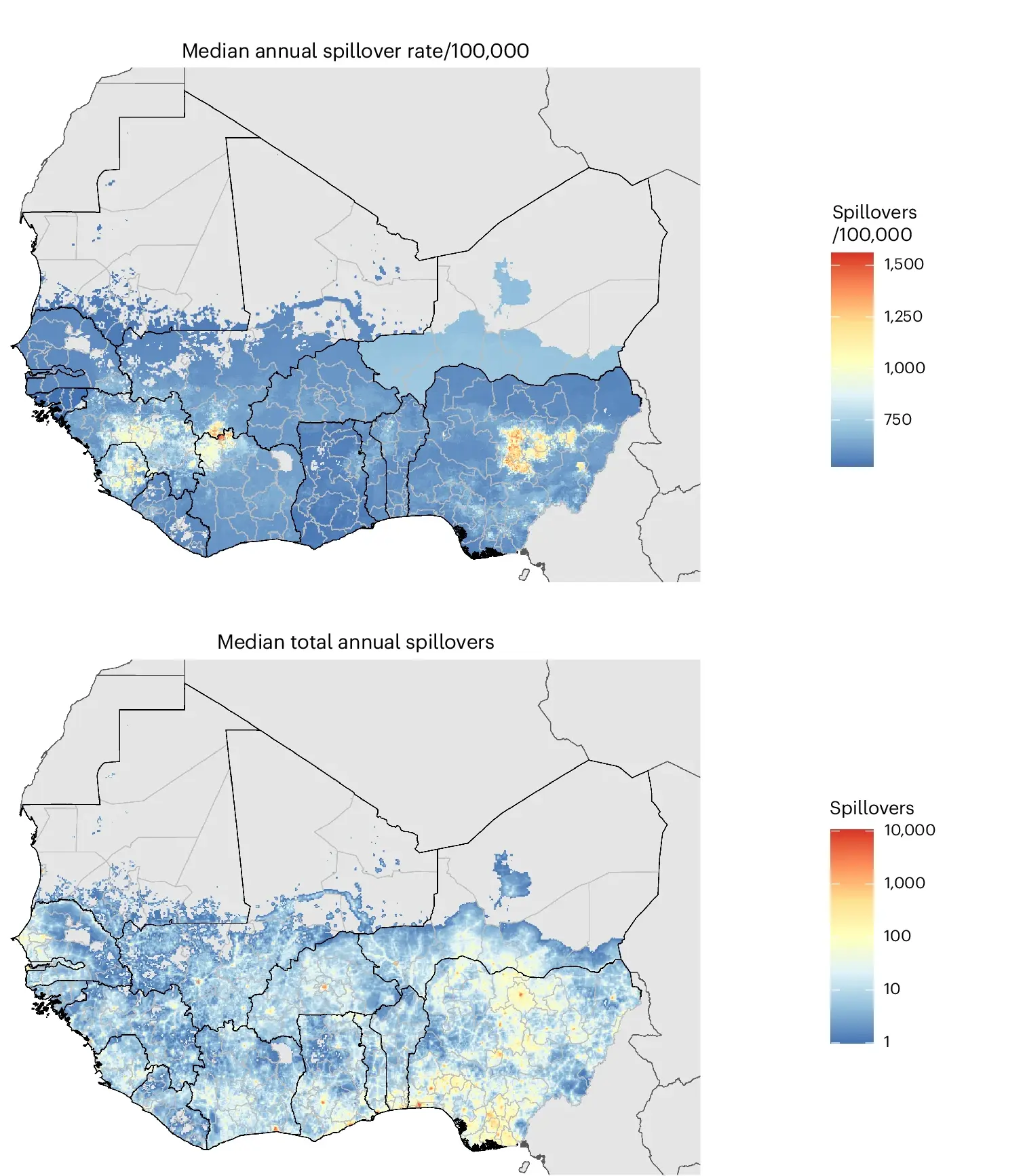

Predicted annual incidence of zoonotic LASV infection per 100,000 population (top) and the median total annual number of zoonotic LASV infections (bottom)

Modelled at the level of 5-km grid cells.

Source: Smith et al., 2024.

In addition, the lack of available countermeasures and its ability to be aerosolized has resulted in Lassa fever’s identification by the United States Centers for Disease Control as a Category A potential biological weapon. This, combined with Lassa fever’s pandemic potential recognition by the WHO, there is significant need for increased attention and bolstered protective measures.

The most notable measure to reduce the global health risk of Lassa fever would be an affordable and available vaccine, as well as targeted therapeutics. Conservative model estimates report that a vaccine would prevent $20 million in lost DALY value and $128 million in societal costs. Fortunately, several are currently in the development pipeline; continued investment is vital as clinical trials encounter extensive difficulties that slow progress in research and development given sporadic outbreaks and logistic barriers in manufacturing and storing sufficient doses.

Preventive measures to reduce exposure risk also include strong hygiene and infection prevention precautions, including appropriate food storage and maintaining rodent-free households. Increased availability and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for health care workers is also paramount to mitigate hospital-acquired infection. Advancements that allow for earlier diagnosis are essential in ensuring patients access care earlier in the disease course. Together, perhaps the most important aspect in preventing LF spread today is increased disease awareness.

“Right now, the best prevention is awareness,” says Acosta. “If someone goes into a region where this is endemic, they need to be aware that this is a real threat.” With pandemic potential, addressing the current burden of the virus and strengthening prevention measures is crucial. At any time, the virus could change to become more transmissible or severe — we need to be ready.

On our radar

- Dengue in China: Last month, a surge in dengue was reported in China. In the city of Guangzhou, a 73% increase in cases was reported in just one week. As the vector’s suitable environment continues to expand globally, the threat of dengue in China, and internationally, is a growing concern.

- Mpox in the UK: Last week, health officials in Britain reported four cases of a new, more infectious variant (Clade Ib) of mpox first detected in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This marked the first cluster of cases of the new variant outside of Africa. Mpox remains a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, as cases across the continent are more than 600% higher than in 2023.

- Dengue in China: Last month, a surge in dengue was reported in China. In the city of Guangzhou, a 73% increase in cases was reported in just one week. As the vector’s suitable environment continues to expand globally, the threat of dengue in China, and internationally, is a growing concern.

BlueDot provides updates, alerts, and critical public health information for Lassa fever and beyond. To keep updated, sign up here to receive every edition of BlueDot Outbreak Insider.