Chandipura, a virus in the same family as rabies, is presumed responsible for 32 deaths in less than a month.

One week ago, India’s National Institute of Virology (NIV) in Pune confirmed that the recent death of a 4-year-old girl in the northeastern state of Gujarat was due to Chandipura, a virus that can invade the human nervous system and whose mortality can reach 60% or higher. The NIV’s announcement substantiated the assessment made two days earlier by BlueDot’s surveillance team, which issued a notice to our Event Alert subscribers about six initial suspected cases of Chandipura virus infection in that region.

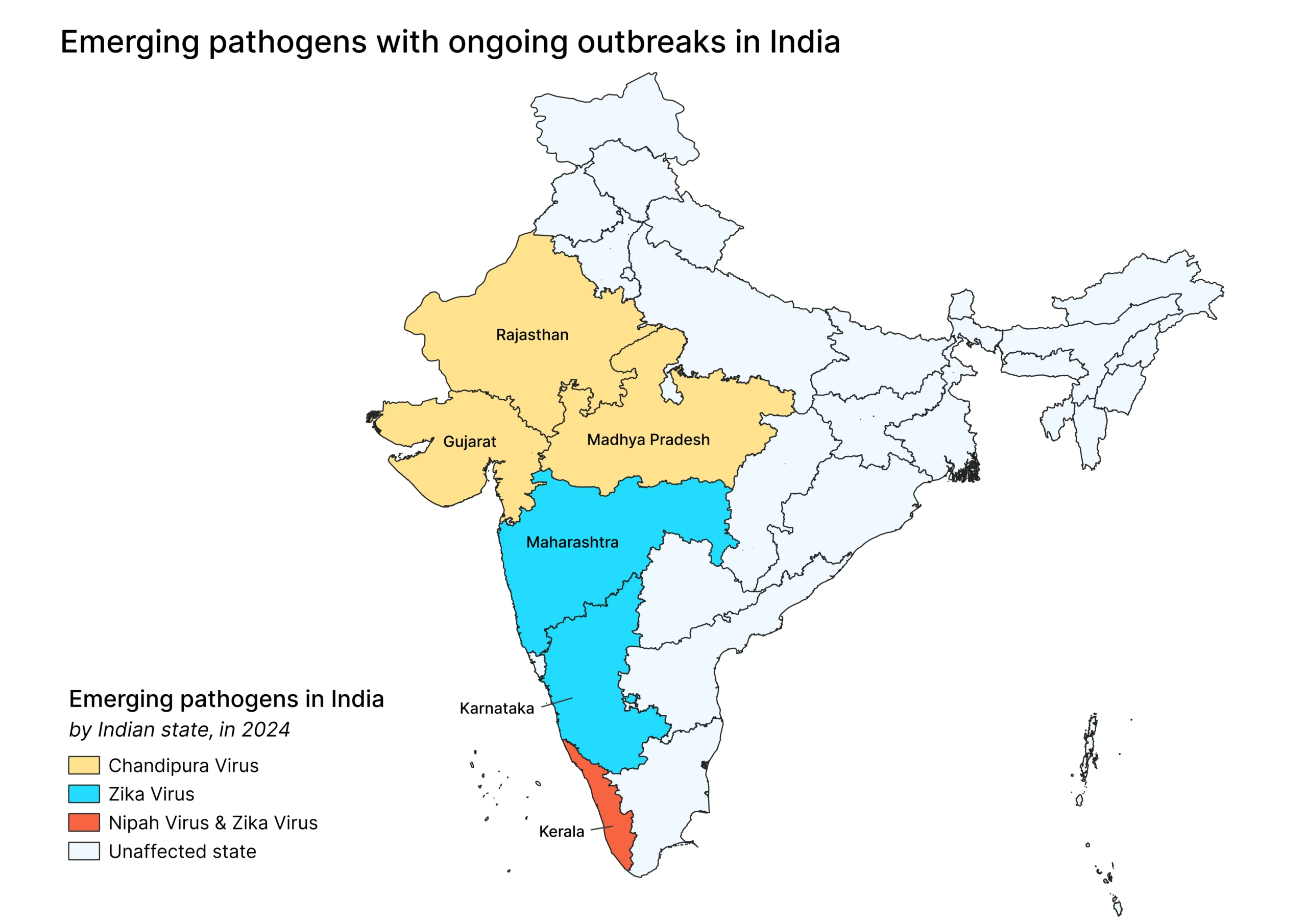

Since then, the situation has taken a striking turn for the worse. Just five days after the NIV’s announcement, Gujarat health officials were reporting a total of 84 suspected cases of Chandipura virus infection, including 32 deaths. Neighbouring Rajasthan was also reporting 2 suspected cases, including 1 death, while Madhya Pradesh also reported a suspected death.

The data reflects a fast-developing situation with a pathogen whose last major outbreak in India came in 2003, when it infected 329 children and killed 183. Because Chandipura virus is transmitted by sandflies, whose populations typically peak during the monsoon and post-monsoon months from June to December, its current resurgence is unlikely to abate soon.

This edition of Outbreak Insider takes an in-depth look at this evasive virus, and how governments and their agencies on all continents can act to prevent further spread.

Chandipura virus: Its history, transmission, symptoms and treatment

Chandipura virus, named for the Maharashtra village where it was first identified in 1965, is classified as a Rhabdovirus, the same family as the rabies virus. Both are RNA viruses that can invade the brain and central nervous system. But unlike rabies, which is transmitted only between specific species of mammals, Chandipura virus is an arbovirus transmitted by insects. Early research in India and West Africa isolated Chandipura virus from Phlebotomine sandflies, the primary culprit in its transmission, native to the tropical regions of Asia, Africa and Europe. Ticks and mosquitoes are also suspected to be potential vectors, though research has not been conclusive.

Chandipura’s virus infection symptoms in humans progress from fever, headache and vomiting to acute encephalitis: convulsions, confusion and hallucinations, seizures and coma, with mortality in up to 60% of cases. Most deaths occur within days of symptom onset. Unlike rabies, whose symptoms usually take several weeks, and sometimes even months to develop, Chandipura’s virus impact is swift, with symptoms appearing within hours following infection.

While there are treatments for seizures and encephalitis, such as (respectively) anticonvulsants and corticosteroids, there is currently no vaccine or antiviral treatment for Chandipura infection that directly targets the virus itself or limits its ability to replicate. (There is one peer-reviewed proposal for a Chandipura virus vaccine, dating back to 2009.) While the disease’s consequences for children can be severe, its impact on adults is less well understood.

Chandipura virus: 3 Top Takeaways

- It’s like rabies, but transmitted by insects. Chandipura virus is a member of the same rhabdovirus family as rabies, and like rabies can invade the human brain and central nervous system. But whereas rabies is transmitted only between mammals, Chandipura’s primary vector is sandflies, making it harder to protect against infection.

- It acts quickly and is highly lethal. Chandipura virus usually progresses rapidly after the onset of fever, headaches, vomiting diarrhea to altered mental status, seizures and coma. Death from infection has occured in around 60% of detected cases, all typically within 24-48 hours from initial infection. There is currently no vaccine or antiviral treatment for Chandipura virus infection.

- Its elusiveness makes it poorly understood. The current outbreak is the first of significance in more than two decades. Its prevalence and impact in adults are unclear, and the role that humans and other species play in the transmission cycle remains a gap in research findings.

What the research can — and can’t — tell us about Chandipura

Chandipura virus has largely evaded researchers’ best efforts to understand it. Outside of the devastating summer 2003 outbreak and a lesser outbreak in 2004, its outbreaks have been sporadic. Prior research from India has also demonstrated a prevalence of Chandipura-neutralizing antibodies in humans, which suggests that the virus has been in broader circulation than one would suspect based on the number of confirmed cases over the years.

All of which adds a layer of scientific mystery to the current outbreak. “With an emerging pathogen like Chandipura virus, the sudden increase in cases raises three distinct possibilities,” explains BlueDot surveillance manager Dr.Marianna Torres Portillo. “The first is that an increase in laboratory and testing capacity means we are simply identifying more cases than before. The second is that the virus may have evolved/changes or mutated in some way. And the third is that there are environmental factors such as habitat changes that play a role and are making transmission of the virus easier.”

Dr. Torres Portillo says it will be some months before researchers can assess any of these potential explanations. But she believes the first possibility is unlikely since India’s highly centralized system for detection means that all samples are processed through the NIV in Pune, which is currently facing a backlog of samples for testing for a range of diseases (i.e., Zika virus and Nipah virus).

Environmental factors could be playing a role: the region’s monsoon seasons, which run from June to September, have intensified in recent years. From 2012 to 2022, both Gujarat and central Maharashtra experienced anywhere from 10% to 30% more southwest monsoon rains than in the three preceding decades. Since sandfly populations peak during the monsoon (June-September) and post-monsoon (October-December) seasons, this could be a contributor to the current outbreak and has the potential to extend it in the weeks ahead.

Where Chandipura might turn up next, and how governments can act

As an arbovirus, Chandipura’s virus range is limited by the habitat of its primary vector. That means it could find its way to the Mediterranean basin. And while the Phlebotomine sandfly is not found in the Americas, that doesn’t mean the disease won’t turn up there.

“Another blind spot in the Chandipura virus research is the role that humans and other species play in the transmission cycle,” says Dr. Torres Portillo. “Can infected humans transmit the virus back to sandflies and mosquitoes? Which other species play a role in transmission? Are humans and other species dead-end hosts? Science has yet to definitively answer these questions.”

Those answers, when they come, will help public health officials in Europe, the Americas and elsewhere understand the risks posed by any imported cases. In the meantime, that doesn’t mean governments or their agencies are bereft of options.

- Public health authorities can move to educate front-line physicians and caregivers about Chandipura virus infection, including recent outbreak locations, so that they are aware of it when patients present with symptoms or have recently travelled to affected regions.

- They can also educate individuals on the consequences of Chandipura virus and on how to prevent infection, such as insect repellants and loose-fitting clothing.

- Governments can establish fumigation plans for regions where sandflies are present, ready for deployment if necessary.

- Governments can prioritize research funding and support vaccine development for Chandipura, and for other neglected tropical diseases.

It’s worth noting that such precautions can also help control arboviruses other than Chandipura virus. In a recent report, the World Health Organization stated that “the risk of emergence and re-emergence of arboviruses with pandemic potential has increased as a global public health threat and will continue to do so in the years to come.”

In recent weeks, India has been in the infectious diseases spotlight as it grapples with significant outbreaks of emerging priority pathogens such as Zika virus, Chandipura virus and more recently Nipah virus.

The Outbreak Insider Update Tracker

Oropouche: In the inaugural June 4 edition of Outbreak Insider, we reported on the ongoing outbreak of another arbovirus, Oropouche, in South America. The virus continues to spread most notably in Brazil, which is now reporting more than 7,300 cases since the start of 2024. The country’s Ministry of Health is warning pregnant women to take extra precautions due to one case of a 28-year-old woman who experienced symptoms associated with Oropouche, followed by a miscarriage at 30 weeks’ gestation. We also reported that “it’s likely just a matter of time” before imported cases are found. Since then both Italy and Spain have confirmed imported cases of Oropouche virus.