As reports of increased cases of HMPV in China arose, social media sparked a misinformation tailspin about the disease and its impact

Shortly after the start of the new year, the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) reported a surge in human metapneumovirus (HMPV) cases in northern China. It took mere days before there was a social media frenzy about a novel virus in China causing overcrowded hospitals and crematoriums, resurfacing memories of COVID-19’s origins and sparking fears about another pandemic.

The alarmism was unfounded. On January 7, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a press release confirming that there had not been an emergency declaration in China for HMPV. In fact, the increase in cases of HMPV is simply part of a seasonal increase in influenza-like illnesses (ILIs), including the flu, COVID-19, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and some others (i.e. adenoviruses, rhinoviruses) across the Northern Hemisphere. The trends reflect Australia’s experience during its 2024 winter, which is often an indicator of what Northern Hemisphere nations can expect. And while the HMPV cases are significant, they are not the result of a novel pathogen ushering in a new pandemic.

With several co-occurring respiratory infections at this time of year, it’s important to uncover what’s really going on,” says Dr. Mariana Portillo, BlueDot’s head of surveillance. “Timely and accurate health information will ensure the appropriate measures are taken to prevent illness and support health systems in need.” This edition of Outbreak Insider takes a closer look at HMPV and how it serves as a cautionary tale for public health misinformation and disinformation.

How Human Metapneumovirus caught global attention

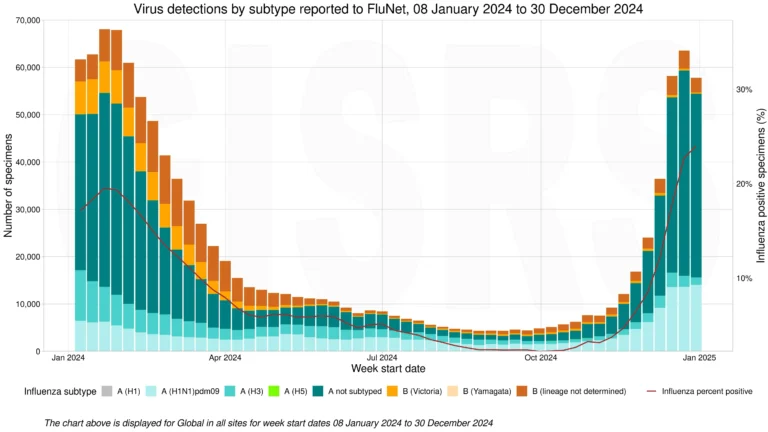

As described in the last edition of Outbreak Insider, ILIs and acute respiratory infections such as seasonal influenza, COVID-19, and RSV are circulating this time of year in the Northern Hemisphere. Cooler and drier air, decreased residual immunity, and more time spent indoors and closer together permit increased transmission. In the last few weeks of 2024, case counts of these illnesses continued to rise around the globe.

Virus detections by subtype, January 8-December 30, 2024

Source: Data reported to World Health Organization FluNet.

HMPV, a common but lesser-known ILI pathogen that can cause upper and lower respiratory disease, was no exception. First discovered in 2001 in the Netherlands, HMPV is part of the Pneumoviridae family of viruses along with RSV. Though not often tested for, elevated case counts began to emerge China in December, where robust surveillance is conducted and weekly reports are published. Despite surging cases of HMPV and other respiratory pathogens, China’s rates are not exceeding what is expected for this time of year, and trends in the northern provinces reflect levels detected in the past two years.

Given a significant ILI season with multiple drivers of illness, including Influenza A, experts did not express concern about HMPV. The disease’s typically mild and short-lived cold and flu-like symptoms, including cough, sore throat, and fever, do not require specific treatments or unique measures for prevention beyond those recommended for other respiratory illnesses. In fact, most people contract HMPV by five years of age. But as with other ILIs, HMPV poses greater risks for severe disease and complications in infants, older adults, and individuals who are immunocompromised or have lung disease such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Yet social media and other news sources sparked the spread of inaccurate information about a novel virus ravaging the population in China, alluding to COVID-19’s emergence in 2020. Context was missing to fully understand what was really occurring on the ground, including that healthcare systems around the globe may be experiencing increased pressure due to several co-occurring infections. Detection and reporting of multiple infections is also a result of new or bolstered surveillance systems implemented post-pandemic, meaning scientists are better able to track and report circulating pathogens than before.

Notably, this is not the first time since COVID-19 emerged that an uptick in respiratory illnesses in China has led to concern about a new pandemic. In late 2023, an increase in Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children resulted in a similar effort by the Chinese health authorities and the WHO to issue reassurances that no unusual pathogens were circulating. The origins of inaccurate health information are not always apparent, but one thing is clear: a primary role of public health is to stop both the spread of infection and incorrect information before serious damage is done.

3 Top Takeaways

- ILIs are intensifying in the Northern Hemisphere. During cooler months, ILIs such as the flu, COVID-19, RSV — and HMPV — circulate. The increased case counts causing concern in China are part of a particularly bad ILI season, which is being seen around the globe.

- Improved technology increases timely and truthful detection of respiratory pathogens. COVID-19 was a catalyst to improve surveillance of respiratory infections. With earlier detection and more precise diagnostics, experts are better able to accurately quantify case counts and trigger the necessary public health warnings.

- Controlling disease hypersensitivity and misinformation is a post-COVID challenge. When COVID-19 struck, mis- and disinformation was rampant amid worry over an unknown illness. Today, identifying false information remains an ongoing effort as individuals work to keep themselves and their loved ones safe.

Managing public health ‘infodemics’

When outbreaks occur, an overwhelming amount of information can circulate. Some evidence may be accurate, but facts may be clouded by misleading or false information. This is referred to as an ‘infodemic’, a term which came into broader awareness during the COVID-19 pandemic when misinformation — information that is inaccurate or contrary to scientific consensus — was running rampant around the globe. Disinformation, or the intentional sharing of misinformation, was also documented. Often, misinformation and disinformation can fill information gaps as scientists gather evidence.

Managing rumors, conjecture, and inaccurate evidence in the throes of a health crisis is an additional public health challenge, with implications for transmission, case counts, and potentially deaths. This has been especially notable throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. In one tragic example of misinformation’s impact, at least 728 people in Iran died in early 2020 as a result of drinking toxic methanol, erroneously believing reports that alcohol could kill the COVID-19 virus inside the body.

Unfortunately, social media can play a negative role in the dissemination of misinformation and disinformation. One meta-analysis reported that up to 29% of social media posts from November 2019 to May 2020 contained COVID-19 misinformation. Among Canadians who use the internet, 96% reported seeing misleading, false, or inaccurate COVID-19 information in the first few months of the pandemic.

In the case of HMPV, China CDC and the WHO have been confronted with misinformation shared in news and on social media. Both organizations swiftly corrected these reports and have largely dispelled concerns, underscoring the ongoing and immense importance of mitigating infodemics. This is no easy task and requires individual and organizational efforts before, during, and after outbreaks occur.

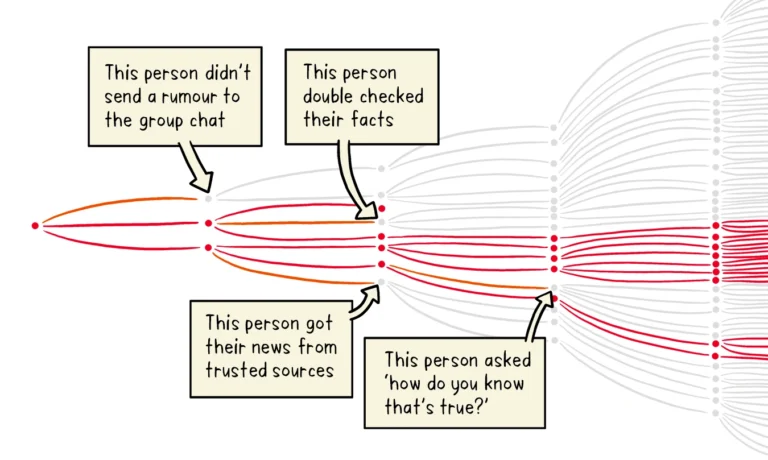

To prevent the spread of misinformation at the individual level, it is first important to learn how to spot it. This involves determining where information came from and appraising the source. For example, is the author or organization credible or is it possible that there is an alternative reason motivating their information sharing (i.e., financial gain from selling a ‘miracle solution’)? In addition, it is crucial to determine if claims can be verified by another source or if there is evidence to support them. And be sure to check bias when reading headlines or stories to challenge pre-existing values and assumptions. Ultimately, the goal is to share accurate data and credible sources with family, friends, and communities.

Stopping the spread of misinformation

Source: World Health Organization.

At the organizational level, promoting health literacy, fact-checking and debunking misinformation, and public communications and community engagement are some examples of interventions to prevent infodemics. Relying on evidence-based research and adhering to it for the development and implementation of public health policies and recommendations is a key step in maintaining public trust and combatting misinformation and disinformation efforts.

Wading through the information pool when there are outbreaks is a lot of work. Fortunately, this is BlueDot’s raison d’être. Using AI and machine learning to capture and filter through tens of thousands of sources, the team of experts at BlueDot works to validate and further investigate outbreaks as they happen.

“There is a lot of noise, which makes it difficult to determine what to focus on,” says Dr. Torres Portillo. “This is where technology helps us at BlueDot: we gather information, verify it, and quickly turn it into actionable intelligence based on factual evidence and our collective expertise.”

On our radar

- Mpox around the globe: Last week, France reported its first case of mpox clade Ib contracted within France from someone who travelled to Africa, where the virus is circulating. This follows China, Belgium, and Kosovo’s first reported cases of clade Ib within the last month among individuals who travelled to Africa. Declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) by the WHO on August 14, 2024, as of January 2025, 14 countries have reported imported cases of mpox clade Ib, with further local transmission detected in at least five countries outside of Africa — UK, Germany, Belgium, France, and China.

- H5N1 in the US: On January 6, the CDC reported that the individual hospitalized in Louisiana with severe avian influenza A(H5N1) had died, marking the country’s first human death of H5 bird flu. The US has confirmed 66 human cases of H5N1 across 10 states since 2024. This week, health authorities in San Francisco, CA reported a presumptive case of bird flu in an adolescent. The multi-state outbreak in dairy cattle, along with widespread outbreak infection in wild birds and sporadic outbreaks detected in poultry and mammals, is ongoing across the nation.

Leveraging technology and subject matter expertise, BlueDot tracks infectious disease outbreaks around the globe. To keep updated, sign up here to receive every edition of BlueDot Outbreak Insider.