The new US administration has pulled the country out of the WHO and paused CDC communications on infectious disease threats. What to know, and what to do next

It has been an exceptionally busy ten days in the world of infectious diseases and public health— not merely because of any particular disease outbreak, but because of measures enacted by the new United States administration in Washington, DC.

In an executive order issued hours following his inauguration on January 20, President Donald Trump directed his administration to withdraw the United States from the World Health Organization (WHO). One day later, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which oversees the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC), issued a directive temporarily prohibiting the release of any public communications until February 1.

That directive held back the US CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, normally released on Thursdays, which provides updates on important infectious disease outbreaks and key learnings, in addition to guidance for public health officials and healthcare providers. In the days that followed, the CDC was also ordered to cease all activities with the WHO until further notice.

This issue of Outbreak Insider takes a closer look at these emerging policy developments, and at some of the steps public and private sector organizations can take amid the uncertainty to protect populations from the health, economic, and social impacts of infectious diseases.

Latest developments: the surprising and the not-so-surprising

The new US administration’s decision to withdraw from the WHO was not unexpected. Back in the summer of 2020, during his first term of office, President Trump first took the formal steps to begin America’s withdrawal from the WHO. That decision was then countered by Trump’s successor, Joe Biden, who blocked the withdrawal from taking effect. It should come as no surprise that President Trump has returned to the course he originally set.

What the withdrawal means for the WHO isn’t entirely clear at the moment. Headquartered in Geneva, the WHO is a United Nations agency whose mandate includes strengthening global infectious disease surveillance and preparing for and coordinating global responses to dangerous epidemics and pandemics — all part of its mission to promote and protect global health. The United States accounted for more than $1 billion of the WHO’s $6.7 billion budget in 2022-23. If those funds aren’t recouped through other revenue sources, the impact of America’s withdrawal will be substantial — especially so if the CDC remains forbidden from working with the WHO in any capacity. The CDC-WHO partnership has been a positive one for improving health and reducing disease risk globally; its dissolution would be a huge setback.

Top Contributors to the WHO Program Budget, 2022-23 (USD million)

Source: World Health Organization.

The directive to withhold public communications from all HHS departments and agencies is not necessarily unusual, as new administrations often implement such pauses during their earliest days in office. However, this particular directive appears to be more wide-ranging than previous ones, as it also cancelled a string of meetings such as external advisory panels and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant proposal reviews. Prior administrations had also never paused the release of scientific publications such as the MMWR throughout its 60-year history; the now-embargoed January 23 edition was expected to include, among other key data, updates on the worrisome H5N1 bird flu outbreak on dairy and poultry farms, as the virus has the potential to spark a pandemic among humans.

What it means for public health

The global impact of these changes is far from certain at the moment. It’s worth noting that, the week prior to Trump’s inauguration, the WHO launched an appeal for $1.5 billion in funding for health emergencies, possibly anticipating a decline in US support. As for the HHS directive, it expires at the end of this week, on Friday February 1. We are likely to learn more about the administration’s plans in the days ahead.

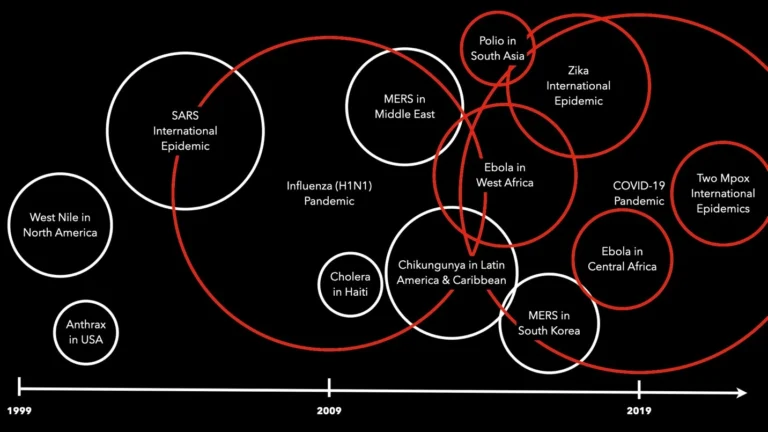

From BlueDot’s perspective, a key concern will be how any eventual policy changes might compromise global disease surveillance and pandemic preparedness and response capabilities. The new US administration comes into office at a time when infectious disease outbreaks have been increasing in frequency, scale and severity. While the COVID-19 pandemic is the most notable example, other instances abound over the past 25 years.

Emerging Infectious Diseases: Timeline, 1999-2024

Source: BlueDot.

West Nile virus was not endemic to North America before 1999. Since then, it has permanently established itself on the continent. The 2015-16 Zika epidemic across the Americas led to severe congenital birth defects in the Americas, with local outbreaks occurring as far north as Florida; affected children now must live with a wide range of debilitating symptoms. Other dangerous outbreaks have included the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), Ebola, Chikungunya and mpox. In the last 16 years alone, the WHO has declared eight Public Health Emergencies of International Concern, averaging one global infectious disease emergency every two years (shown as red circles).

How organizations can prepare amid uncertainty

Since the new US administration’s full policies and plans remain unclear at the moment, those working in fields pertaining to infectious disease prevention and control will need to wait until the dust settles. What is certain, however, is that infectious diseases don’t wait for communications embargoes to be lifted, or for WHO dues to be paid, before emerging and rapidly spreading across the globe.

3 Top Takeaways

- Disruptive global health policy changes are afoot in Washington. The new US administration plans to withdraw from the World Health Organization. It has also paused all public communications from the US CDC and other HHS departments until February 1, amid speculation of further policy changes to come.

- Multiple outbreaks are unfolding right now, with more threats coming. They include the threat of an influenza pandemic triggered by avian H5N1. As political speculation swirls, infectious diseases continue to pose an ever-increasing threat to human and animal populations worldwide.

- Diversifying sources of infectious disease surveillance and intelligence is essential. As WHO and CDC efforts to prepare for and respond to global outbreaks may become compromised, public and private sector organizations can partner with independent, third-party organizations that curate and analyze diverse official and unofficial sources of infectious disease data and intelligence.

Many organizations depend upon timely, accurate, and unbiased infectious disease surveillance data, whether it’s public health authorities working to protect populations against dangerous global pathogens, pharmaceutical companies developing vaccines and therapeutics to prevent or control outbreaks, global enterprises protecting their workforces and supply chains from disruption, or healthcare providers protecting their patients, their communities, and themselves from dangerous diseases.

While the WHO and US CDC are very important sources of data, they are not, and should not be, the only sources. For organizations that value early warnings and timely insights on infectious disease threats arising anywhere in the world, this is an opportune moment to re-examine and re-invest in reliable, diverse, and unbiased sources of infectious disease data.

BlueDot, for its part, believes strongly in the need for independent, authoritative, third-party sources of data and intelligence on global infectious disease threats. The company’s founding was inspired by challenges uncovered during the original SARS epidemic of 2002-03, when official information on the outbreak was not forthcoming, leading to serious global health, economic, and social consequences. Diversifying data sources and using advanced data analytics to infer the hidden scale of an outbreak can minimize blind-spots arising from weak public health systems or governmental decisions to withhold information on an emerging outbreak.

Since its founding, BlueDot has amassed its own extensive network of both official and unofficial sources of data on global infectious disease threats and their drivers. Its combination of human expertise and AI-driven large language models empowers the organization to quickly sift through hundreds of thousands of data sources across the world’s many languages, including wastewater surveillance, outbreaks in livestock and wild animals, and insect vectors. BlueDot’s surveillance team of infectious disease and public health experts is able to separate fact from fiction and identify emerging outbreaks in their earliest stages and ahead of official reports — as it did during COVID-19.

“When it comes to infectious disease surveillance, you have to look around every corner,” says BlueDot founder and CEO, Dr. Kamran Khan, a practicing infectious disease physician. “We are continuously seeking out new data sources that offer a different vantage point and perspective on infectious disease threats. This is the one thing we do all day and every day, and we’re committed to it because the world needs it now more than ever.”

On our radar

- Marburg in Tanzania: An outbreak of Marburg virus, a zoonotic emerging pathogen in the same family as Ebola that originates in fruit bats, has infected 10 people and killed 9 in the east African country of Tanzania as of January 23. The outbreak is centered in the country’s northern Kagera region bordering Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda, raising concerns of regional spread and health system impacts given its high case fatality rate.

- Mpox in multiple locations: The United Kingdom reported its seventh case of mpox clade 1b in January, in a traveler recently returned from Uganda. China reported its first cluster of mpox clade 1b cases, for which the index case was a traveler returning from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. And the west African nation of Sierra Leone declared a public health emergency following reports of two mpox cases within four days, though the clade remains unknown. Clade 1b is a newly-identified strain of mpox, which has now been reported in 12 countries outside of Africa.

Leveraging technology and subject matter expertise, BlueDot tracks infectious disease outbreaks around the globe. To keep updated, sign up here to receive every edition of BlueDot Outbreak Insider.