Climate change has led to rising flood risk from hurricanes and monsoons to torrential rains, bringing infectious diseases in their wake

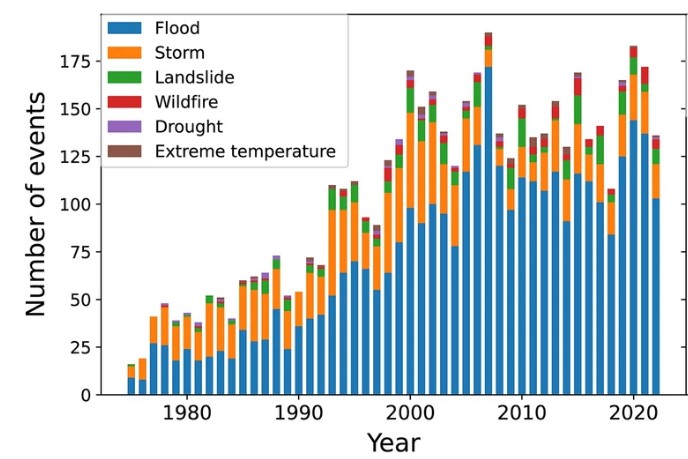

As the earth warms due to climate change, its impacts — record-breaking temperatures, melting glaciers, warmer oceans — create ideal conditions for extreme weather events. From heatwaves and droughts to hurricanes and floods, natural disasters are increasing in frequency and intensity. In 2020 alone, there were 132 extreme weather-related disasters, affecting nearly 52 million people and causing 3,000 deaths.

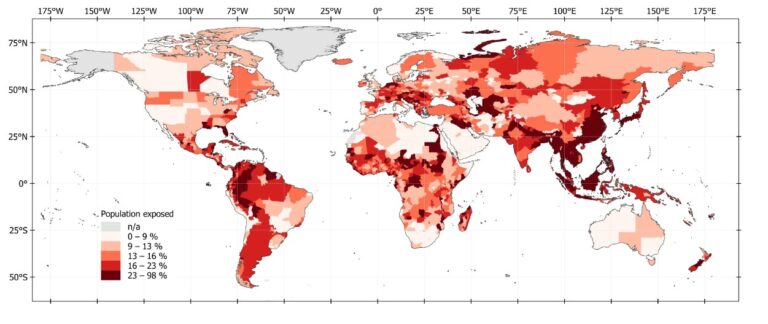

Floods are the most common natural disaster, representing approximately 40–50% of all events. More than 1.65 billion people were affected by floods between 2000 and 2019. Nearly a quarter of the world’s population is exposed to significant flood risk, of which almost 90% are in low- and middle-income countries. As floods become more frequent, annual flood exposure is estimated to increase 14-fold over the next 75 years.

Natural disaster events, 1975–2022

Source: Jonkman et al., 2024.

Population exposed to flood risk

Source: Rentschler et al., 2022.

Floods present significant economic impacts resulting from shuttered facilities and business interruptions. Every year, floods cause $40 billion in damage globally, which has amounted to more than US$1.3 trillion in economic damages from 1990 to 2022. China sustained the most economic damage during that period at US$442 billion, followed by the US at US$135 billion. The economic risks and impacts, which can leave businesses with no choice but to shut their doors, are often underestimated.

And once the worst of the weather has passed, a second wave of damage emerges: infectious diseases. From waterborne and vector-borne diseases to respiratory and cutaneous infections, these outbreaks represent a significant post-flood threat. Damaged water treatment plants and overflowing sewage systems can exacerbate infectious disease risks. Contaminated water and food, poor sanitation, population displacement, and overcrowding, along with interrupted vaccination and vector-control programs and disrupted healthcare services, allow pathogens to more easily ravage communities. This edition of Outbreak Insider examines the infectious diseases that often spread in the aftermath of floods.

3 Top Takeaways

- Floods are the most common, and deadly, natural disasters around the world. Affecting billions of people globally, the impact of floods is set to worsen as exposure is projected to increase 14-fold by the year 2100.

- Infectious diseases are among the most concerning post-flood threats. From waterborne and vector-borne diseases to respiratory and cutaneous infections, health risks emerge within weeks and persist for up to two years following a disaster.

- Flood preparedness and risk management are the focus in reducing health effects. As flooding increases in frequency and intensity around the globe, measures to prepare, respond, and recover from events should be prioritized to ensure timely and widespread action when disasters strike.

- Floods are the most common, and deadly, natural disasters around the world. Affecting billions of people globally, the impact of floods is set to worsen as exposure is projected to increase 14-fold by the year 2100.

Opening the floodgates to infectious diseases

In the wake of flooding, communicable disease risk significantly increases. When people move to safer locations, direct contact with contaminated water and lack of sanitation leads to skin infections and waterborne infectious diseases, such as E. coli, hepatitis A and E, and Vibrio-related diseases including cholera. At the same time, rodent-borne diseases including leptospirosis emerge due to exposure to rodents or urine-contaminated soil, water, or food. In oft-overcrowded emergency shelters, measles, meningitis, and acute respiratory infections can flourish. Standing water also gives rise to expanded vector breeding grounds and mosquito-borne diseases, including dengue, malaria, and Zika virus.

Children, older adults, and women — especially if pregnant — are at increased risk for poorer health outcomes of infectious diseases during disaster events. Risks are exacerbated in lower-income locations with limited resources for emergency response and public health. Disease hazards begin emerging as early as two weeks post-disaster, but can persist for two years after an event. These events also disrupt management of other endemic and underlying health conditions.

The infectious disease hazards of floods are not just a public health issue but an enterprise risk issue. Businesses must anticipate the logistical and financial needs not only for flood damage repair but also for health risks.

Case 1: Infectious disease and hurricanes in the United States

Over time, flooding has become increasingly more common along the US coastline, where more than 40% of Americans reside and more than $1 trillion in infrastructure is at risk. In 2024, infrastructure damage from hurricanes Helene and Milton are expected to exceed $50 billion, joining the ranks of Hurricanes Katrina (2005) and Sandy (2012) in terms of economic devastation.

In the first few weeks following hurricanes, exposure to floodwater increases cases of waterborne diseases such as E. coli, Legionnaires’ disease, and cryptosporidiosis, as well as Vibrio vulnificus, a flesh-eating bacteria found in warm water. After Hurricanes Helene and Milton moved through, around 40 cases of Vibrio vulnificus were reported in Florida. To date, the state has seen a total of 81 cases and 16 deaths in 2024, exceeding the 74 cases reported in 2022 — the year Hurricane Ian struck Florida. Another flesh-eating bacteria, Streptococcus pyogenes, led to the death of a woman in Houston after exposure to Hurricane Harvey’s floodwaters in 2017.

In addition, the standing floodwater left behind by hurricanes allow arboviruses like West Nile and dengue to spread. Cases of West Nile virus rose in Louisiana and Mississippi following Hurricane Katrina, as did other airborne pathogens: nearly 50% of inspected homes across New Orleans had visible mold growth, which contributed to respiratory infections such as toxic pneumonitis.

Case 2: Infectious disease and typhoons in the Philippines

In the last month, the Philippines has been hit with six back-to-back tropical cyclones moving through the country’s northern regions and affecting approximately 10 million people. At least 171 people have died, hundreds of thousands of people have been displaced, and many homes have been damaged or destroyed. This succession of storms was atypical for the Philippines, and the extensive infrastructure damage has yet to be fully assessed.

Like hurricanes in the US, typhoons result in large areas of stagnant water, providing an essential prerequisite for mosquitoes to breed — and spread infectious diseases. BlueDot released an event alert on September 16 about spiking dengue cases in the Philippines amid several tropical storms. From October 6-19, over 20,000 cases were reported, and another 17,000 were reported from October 20-November 2. By November 16, the country had recorded nearly 341,000 cases throughout 2024, which was an 81% increase compared to the same period in 2023.

Following Typhoon Carina in August, a rise in leptospirosis cases triggered the activation of the Surge Capacity Plan across hospitals in the National Capital Region. As of October 5, more than 5,800 cases have been reported this year, which is a 16% increase compared to the same period last year. Over time, leptospirosis cases have been increasing in the Philippines, largely due to the many water-related natural disasters that strike the nation.

Case 3: Infectious disease and flooding in Pakistan

Pakistan has been identified as the world’s fifth most vulnerable country to long-term climate change. In 2022, one-third of the country was submerged in widespread flooding following monsoon rainfall. The disaster affected over 33 million people, damaged more than 2 million homes, and destroyed more than 2,000 healthcare facilities. Roads, railways, and other infrastructure were also heavily damaged. The total damages are estimated to exceed US$15 billion, marking a substantial hit on the already fragile economy.

Following the 2022 flood, the country saw its worst malaria outbreak since 1973. At least 2.6 million cases were reported, a five-fold increase from the 500,000 cases a year prior — though many more cases were suspected. An increase in dengue was also observed, with nearly 42,000 confirmed cases in the country as of October 11, 2022. Although both mosquito-borne diseases are endemic to the nation, disrupted vector control programs and a shortage of mosquito nets and repellants amidst the flood devastation contributed to increased vector-borne outbreaks.

Waterborne diseases, including cholera and typhoid, also increased due immense population displacement, poor sanitation, lack of clean water, and overcrowding. An analysis of suspected infectious disease notifications to Pakistan’s Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) system between September and December 2022 identified approximately 340,000 cases of acute diarrhea, 16,000 cases of typhoid, and 14,000 cases of suspected cholera. Skin, eye, and respiratory infections were also widespread. With several concurrent outbreaks, the healthcare system faced challenges in providing adequate treatment given the lack of resources.

Moreover, as BlueDot reported back in May 2023, health officials in Sindh and Karachi issued an advisory warning about increasing trends with respect to typhoid drug resistance (XDR-TF). Cases of XDR-TF have also been identified in Southeast Asia and eastern and southern Africa. Typhoid drug resistance is a matter of global concern given the increased risk of outbreaks due to flooding.

On our radar

Mpox in Angola: On November 16, the first case of mpox in the country was reported in a 28-year-old woman, making Angola the twentieth African nation with confirmed mpox cases. Just last week, the woman’s child also tested positive. Angola shares a large border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the epicenter of an mpox outbreak where nearly 50,000 suspected cases and more than 1,000 deaths have been reported.

Vaccine-derived Polio in Poland: Last week, poliovirus type 2 was detected in wastewater samples in Poland, where the last case of wild-polio was recorded in 1984. The 2023 vaccination rate among 3-year-olds was 86%, falling below the 95% level needed to prevent spread. In response, sewage testing and surveillance of acute flaccid paralysis in children have increased, and vaccine stocks and information campaigns have been bolstered.

Avian influenza (H5N1) in North America: A child in California tested positive for avian influenza (H5N1) last week, following on the heels of reports of the first human H5N1 avian influenza case in Canada, in a teenager in British Columbia who remains in critical condition In both cases, the sources of exposure remain unknown. Most human cases to date are in farmworkers, but experts are concerned about what these two cases may mean for spillover risk and viral adaptation supporting more efficient human infection.

As natural disasters become a bigger threat around the world, disaster management systems are vital. Strong public policies, vector-control programs, surveillance, and public awareness campaigns are some strategies to reduce the health effects of flooding and other events. Given that infectious diseases claim the lives of more than 700,000 people in the acute phase following a natural disaster, these measures can prevent serious illness and death, especially in lower-income countries who are most affected by outbreaks.

“The hardest hit nations also happen to have the right conditions to allow for the flourishing of infectious diseases,” says Andrea Thomas, PhD, BlueDot’s head of epidemiology. “But with climate change, the conditions could be ripe for the perfect storm of infectious diseases anywhere in the world.”

Leveraging technology and subject matter expertise, BlueDot tracks infectious disease outbreaks around the globe as they are happening. To keep updated, sign up here to receive every edition of BlueDot Outbreak Insider.