The U.S. government shutdown demonstrates how infectious disease data sources can dry up — and how third-party surveillance sees in the dark

The recent US government shutdown, lasting 43 days and furloughing around 670,000 federal employees, disrupted a multitude of programs and services. Not least among these were health research, disease surveillance, and expert public health guidance, all of which were halted just as seasonal respiratory illnesses returned.

As federal operations resume, state and local health departments — who are accustomed to depending upon federal data and guidance for their own planning and decision-making — are trying to fill the gaps. With government funding only secured through January, another data blackout is possible.

Shutdowns are just one example of how gaps in official surveillance data can emerge, with potentially damaging consequences for those who rely upon it. In conflict zones, which are afflicted by mass displacement and health infrastructure damage, tracking and testing for infectious diseases is especially difficult. And returning travelers can often point to outbreaks in places where local authorities have yet to fully ascertain them. Infectious diseases can capitalize on all these situations, spreading quickly and putting response efforts at a major disadvantage.

“Infectious disease surveillance is a complex web of official and unofficial sources that need to be analyzed and contextualized,” says Andrea Thomas, BlueDot’s Head of Epidemiology. “Data gaps pose immeasurable risks for human lives and healthcare systems around the world, emphasizing the importance of reliable and timely reporting.”

With the increasing frequency and scale of emerging infectious diseases, prompt, accurate, and multi-source monitoring systems are an ever-growing public health and enterprise need. This edition of Outbreak Insider investigates how these situations impact surveillance data, and how BlueDot’s techniques are used to fill in the gaps.

A synopsis of disease surveillance history and challenges

Disease surveillance is the bedrock of public health. Its origins date back to the 1300s in the Venetian Republic, when a system to detect and isolate ships with infected passengers was established. Over the following centuries, surveillance morphed from detecting disease to complex systems of data collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination to guide action. Today surveillance is vital for risk factor monitoring, epidemic detection, disease burden estimation and resource allocation, and informing vaccine and medication research and development.

But surveillance is also continuously beset by limited monitoring capabilities and resources, fragmented systems and coordination, non-standardized data collection and sharing, and political and economic pressures. When blind spots occur, morbidity and mortality increase, interventions are rendered less effective, and substantial economic damage can ensue.

When the dashboard goes dark

On October 1, the US federal government shutdown caused non-essential functions to cease. Caught up in the mix was the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Infection (CDC), the country’s nationwide beacon of infectious disease intel. As dashboards dimmed and analysis abated, North America was entering its influenza-like illness (ILI) season. In the absence of updated disease trends, weekly reports, and expert analysis, state and municipal governments were left with a limited, patchwork perspective on nationwide disease activity and external threats.

What resulted was “DIY surveillance.” States are mandated to conduct infectious disease surveillance, such as wastewater monitoring, but capacity is variable. And their lines of communication with the CDC, which provided a nationwide perspective that kept them abreast of developments in surrounding regions, are not as robust as they have been in the past. With the data blackout, early outbreak warnings for influenza, COVID-19, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) were limited, leaving local health departments more susceptible to delayed responses.

Even with the shutdown now over, CDC job cuts and unstable funding create ongoing risks for data availability. The flu alone resulted in 47 million illnesses, 610,000 hospitalizations, 27,000 deaths across the US during last year’s season (October 2024 to May 2025), demonstrating the immense cost to human lives and the healthcare system.

Get trusted, near real-time visibility to fill in the data gaps

When official reporting slows or stops, BlueDot’s intelligence platform continues to track and verify emerging threats around the world. Stay informed with continuous, expert-reviewed updates tailored to your organization’s needs. Contact BlueDot to learn more.

War obscures warning signs

In a very different manner, ongoing violence in Sudan has also disrupted surveillance systems, contributing to a massive cholera outbreak. More than 50,000 cases and 1,350 deaths have been confirmed since the start of the year as millions of people were forced into camps that were overcrowded, unsanitary, and lacked clean water. Underreporting and delays in infection detection meant the outbreak rapidly grew out of control. And cholera was just one of several concurrent outbreaks, along with measles and malaria, that were reported in Sudan.

Instability due to conflicts, such as the one in Sudan, is another common barrier to disease surveillance. Mass population displacements and damage to health infrastructure, strain tracking, testing, and response systems. Before long, the absence of proper surveillance lets pathogens silently circulate among vulnerable populations.

Beyond missing early indicators of outbreaks, limited surveillance creates gaps in data that are used to confirm disease strains and inform preventive measures like vaccination and vector control. In the Gaza Strip, strained healthcare and lab systems led to insufficient information about an unknown respiratory illness, raising questions about the possibility of a new influenza strain. Last year, the detection of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) amid Gaza’s limited surveillance capabilities fueled concerns about polio transmission.

Over 100 armed conflicts are ongoing worldwide. The inability to track real-time trends and the risk associated with unknown strains or symptomatology without proper lab capacity pose acute and downstream impacts. Conflict-affected regions, humanitarian agencies, and global public health bodies grapple with uncoordinated data collection, analysis, and response — before widespread outbreaks put them in damage control mode.

What resulted was “DIY surveillance.” States are mandated to conduct infectious disease surveillance, such as wastewater monitoring, but capacity is variable. And their lines of communication with the CDC, which provided a nationwide perspective that kept them abreast of developments in surrounding regions, are not as robust as they have been in the past. With the data blackout, early outbreak warnings for influenza, COVID-19, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) were limited, leaving local health departments more susceptible to delayed responses.

Even with the shutdown now over, CDC job cuts and unstable funding create ongoing risks for data availability. The flu alone resulted in 47 million illnesses, 610,000 hospitalizations, 27,000 deaths across the US during last year’s season (October 2024 to May 2025), demonstrating the immense cost to human lives and the healthcare system.

3 Top Takeaways

- Data blackouts come in many shapes and sizes. Political instability, lack of resources and infrastructure, and inhibited data collection and sharing, such as during government shutdowns and conflicts, are factors underlying infectious disease surveillance gaps.

- The implications of impaired disease monitoring can be immense. When outbreak detection is delayed or missed, diseases can spread quickly as containment measures lag, leading to lost productivity, lost lives, and strained health systems.

- Diversified data sources provide effective surveillance. Tracking infectious diseases is an increasingly complex challenge in a more globalized world. Integrating more inputs into a surveillance framework allows for a timelier and more accurate picture of disease dynamics.

Blurred Borders

Earlier this summer, Taiwan, Macau, and the US issued health alerts for chikungunya in Guangdong, China as cases linked to travel emerged. While China had reported an outbreak, it was the travel-related cases that helped establish just how extensive it was. Similarly, in September, a Level 2 health alert for chikungunya in Cuba was issued by the US after returning travelers were diagnosed. Media reports pointed to widespread symptoms among the island nations’ residents, yet official case counts were unavailable.

These outbreaks demonstrate how travel-related cases can unveil surveillance gaps. Variability in local surveillance, underreporting from travelers and countries, and unstandardized and uncoordinated monitoring and reporting processes mean pathogens can reach new countries before outbreaks are even noticed. In some instances, such as Guangdong, international health alerts for imported cases can be a sign of the magnitude of an outbreak — or even a signal that an undiscovered outbreak is occurring.

Whether due to political and economic concerns or suboptimal monitoring, traditional surveillance methods are often insufficient in providing real-time and reliable travel data before diseases get transmitted.

Closing the surveillance gap

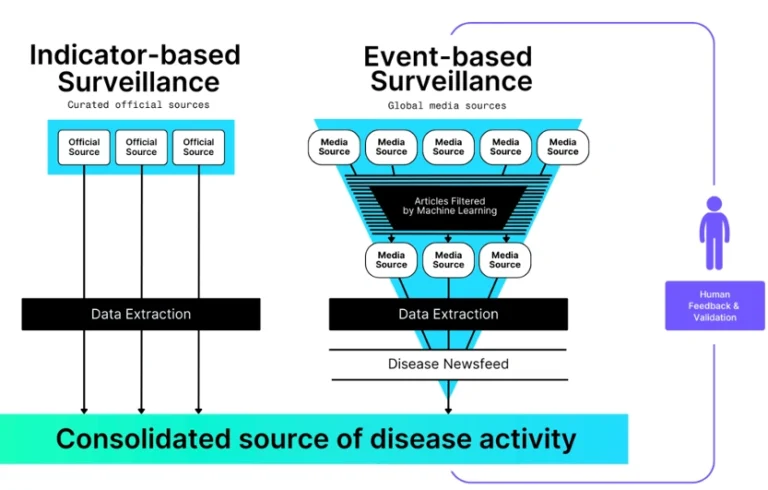

From BlueDot’s perspective, given the frequency and unpredictability of all these data delays and interruptions, any organization that relies on infectious disease surveillance cannot rely on official sources alone. BlueDot combines AI with human intelligence to scan, filter and analyze official and unofficial sources across languages around the globe, allowing us to identify and report on important events for over 190 diseases.

Indicator-based surveillance, such as case counts, hospitalizations, and deaths, and event-based surveillance, such as media reports and digital platforms (like internet search trends on symptoms), offer enormous pools of data from diverse sources. Unusual signals can prompt early-warning signs of outbreaks of both well-understood and emerging diseases. They can also provide valuable information to predict risk for nearby regions and travelers.

“Our methodology detected a cluster of ‘unusual pneumonia’ cases in Wuhan, China on December 31, 2019 — a week before the US CDC and the WHO issued statements,” says Thomas. “We sent out an alert as soon as we knew and notified clients about highly connected areas at risk.”

BlueDot’s Global Disease Surveillance Engine

Triangulating near real-time data from multiple sources overcomes inconsistent official data to support faster detection and response, which is critical in fast-moving outbreaks with limited formal reporting. Incorporating expert analysis is essential to see the forest for the trees. Validation of signals, putting them into context, and determining actionable insights help separate notable events from noise.

Advancements in technology have transformed the landscape of disease surveillance, overcoming long-standing challenges such as delayed reporting, fragmented systems, and barriers to data sharing. By harnessing the capabilities of BlueDot, organizations can enhance their ability to detect, analyze, and respond to outbreaks swiftly and effectively. Staying ahead of emerging threats is more achievable than ever — empowering public health professionals and decision-makers to protect communities with timely, reliable information.

On our radar

- Poliomyelitis in Germany: On November 12, Germany’s national public health authority detected wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) — the rare, naturally occurring polio endemic only in Afghanistan and Pakistan — in a wastewater sample in Hamburg. Marking the country’s first environmental detection of WPV1 since 2021, the sample appears to be linked to a strain circulating in Afghanistan. Challenges in global polio eradication pose risks for importation around the globe.

- Pertussis in Argentina and the US: Sharp rises in pertussis (or whooping cough), a vaccine-preventable disease, have been reported in Argentina and the US. The former saw a health alert issued in the Buenos Aires province after 5 infant fatalities, with cases exceeding 3,700 nationally. Similarly, a health alert was issued in Texas as cases surpassed 3,500 across the state. Infants, who are too young to be vaccinated, are at increased risk, highlighting the importance of up-to-date immunization status — especially among those in close contact.

- Marburg in Ethiopia: The East African country is facing its first-ever outbreak of Marburg virus, which can cause severe hemorrhagic fever, in the country’s southern region. A total of 9 cases and 3 deaths have been confirmed to date, and 17 suspected cases have been identified in the Jinka city region. The virus is the same strain that has been reported in previous outbreaks in East Africa. There is no vaccine for Marburg, whose average case fatality rate is 50%.

Leveraging technology and subject matter expertise, BlueDot tracks infectious disease outbreaks around the globe as they are happening. To keep updated, sign up here to receive every edition of BlueDot Outbreak Insider.