Climate, conflict, and crumbling infrastructure are fueling the rapid global spread of the deadly bacterial disease

Cholera, the waterborne bacterial disease that spurred the construction of urban sanitary sewers and waterworks in the 19th century, is once again becoming a scourge to global health.

Last month, 62,330 new cases of cholera and/or acute watery diarrhea (known as AWD, of which cholera is the most frequent cause), and 527 cholera-related deaths were reported across 20 countries and territories around the world. Global cases since January have already surpassed 300,000 and led to 3,500 deaths. And for the first time in half a year, the cholera vaccine stockpile fell below the necessary emergency reserve, threatening global capacity to respond as outbreaks intensify.

Following years of declining cholera cases, the bacterial infection made a resurgence in 2021. Since then, yearly outbreaks have only worsened. Twenty-eight countries have reported outbreaks so far this year, with the majority of cases in the Eastern Mediterranean and African regions. And those outbreaks are becoming increasingly deadly. Despite lower case counts compared with June 2024, deaths this year are up 38%, pointing to gaps in timely access to care.

Humanitarian crises caused by events such as floods and armed conflict are major drivers of increased cholera risk, as they impair healthcare infrastructure and limit access to urgently needed care. Up to 4 million cases and 143,000 deaths are estimated every year, and more than 1 billion people are at risk for infection. Both the WHO and the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have sounded the alarms. And recent evidence points to circulation of antimicrobial resistance in cholera, further compounding widespread outbreaks and containment challenges.

“Antimicrobial-resistant cholera is likely circulating in countries with the largest outbreaks, where diagnostic capabilities are limited,” says Dr. Mariana Portillo Torres, BlueDot’s head of surveillance. “Without appropriate diagnosis, ineffective antibiotics may be prescribed, meaning people are not only receiving suboptimal treatment but antibiotic resistance is exacerbated.”

Given the sharp and sustained rise in cases, and the emergence of antimicrobial-resistant strains, cholera outbreaks are expected to worsen — and it will take sustained effort to contain them.

Global cholera cases are spreading faster and becoming deadlier

Cholera is a bacterial disease caused by Vibrio cholerae transmitted through the ingestion of contaminated water or food, one with a remarkable history as both a health menace and a catalyst of human ingenuity. The disease originated in South Asia and spread widely in the 19th century, the result of ships transporting contaminated bilge water from the Bay of Bengal. Cholera was the main driver of the mid-19th century sanitation movement in Europe and its colonies, leading to the establishment of sewage systems and clean water provisions in many parts of the world.

Today, those most at risk live in locations still without access to safe drinking water, sanitation, or hygiene. Not everyone who gets cholera becomes ill. But for ten percent of people, cholera can lead to life-threatening watery diarrhea and vomiting, quickly causing dehydration and shock. If untreated, it can kill people within hours.

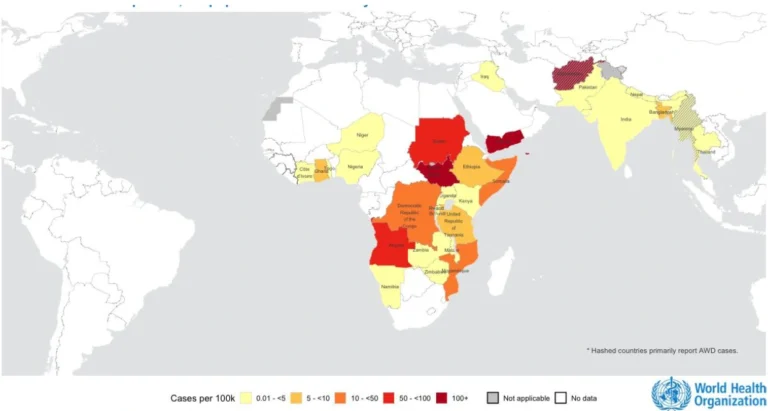

Between January and June 2025, 305,903 cases and 3,522 deaths have been reported across 28 countries. The hardest hit regions are the Eastern Mediterranean (159,414 cases, a region which encompasses the Arabian peninsula and its surroundings), Africa (143,762 cases), and South-East Asia (2,727 cases). Of these, cases are most widespread in Africa, with 19 countries reporting cases. Actual case counts are likely higher as reports are delayed or the disease goes underreported.

Cholera and AWD cases per 100,000 cases, Jan. 1-June 29, 2025

Source: World Health Organization, Multi-country Outbreak of Cholera External Situation Report n. 28, published July 24, 2025.

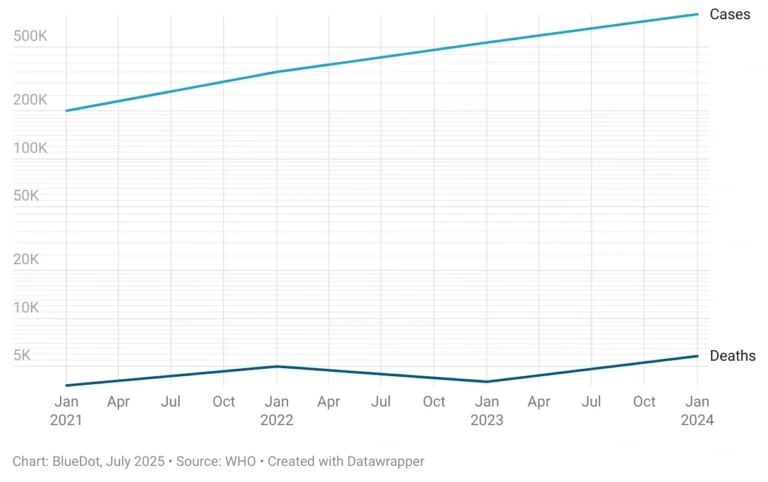

The fight against cholera led to declining cases for several years. But in 2021, cases began rising as the COVID-19 pandemic, along with climate-related disasters and conflicts, disrupted health systems. In 2022, more than 30 countries reported outbreaks — twice the usual amount — prompting the WHO and Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFCC) to officially recognize a multi-country resurgence.

In January 2023, the WHO labelled cholera a Grade 3 Emergency, its highest level, as countries such as Malawi, Mozambique, and Syria faced their worst outbreaks in decades amid depleted vaccine stockpiles. Climate events and conflict worsened outbreaks across Africa, Asia, and parts of the Americas in 2024, which saw a 50% increase in cases over the year prior. Outbreaks have also become deadlier, leading to the decade-high case fatality rates.

Cholera Cases and Deaths, 2021- 2024

Source: BlueDot, July 2025. Data source: WHO, created with Datawrapper.

Particularly hard hit this year are Angola (27,033 cases), Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC; 34,192 cases), South Sudan (62,903 cases) and Sudan (32,359 cases) in Africa and Afghanistan (68,031 cases) and Yemen (42,162 cases) in the Eastern Mediterranean. Several of these have contributed to the 29 new emergency requests seeking vaccine doses between January and June, up from nine last year. The Africa CDC has identified cholera as a top challenge, and cholera outbreaks are rapidly moving toward a health emergency of regional concern.

Often, several concurrent diseases simultaneously overwhelm available health services. In Yemen, for example, an 87% increase in cholera cases was reported last month compared with May as the nation also combatted co-circulation of both measles and dengue. Similarly, South Sudan is navigating its worst and longest cholera outbreak while also confronting regional outbreaks of mpox, hepatitis, and measles. Outbreaks are further complicated by low vaccination rates, such as in Sudan, where cholera vaccine coverage is only 5.6%.

Europe’s risk for cholera is low as it does not confront the same sanitation and hygiene challenges. Yet, the region has seen a few cases linked to travel or exposure tied to at-risk regions. For example, four domestic cases in Germany and the UK emerged in February 2025 following the ingestion of holy water imported from Ethiopia.

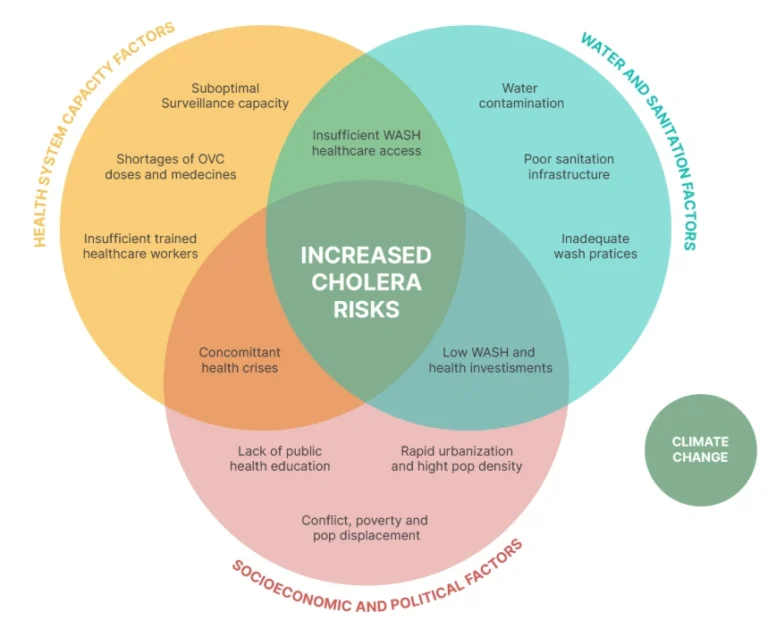

Complex factors combine to increase cholera risk

Ongoing outbreaks are a complex interplay of several factors. At the forefront is unsafe water, poor sanitation, and inadequate hygiene practices. These intersect with socioeconomic factors such as rapid urbanization and lack of public health education, as well as health system capacity factors such as limited surveillance and prevention and treatment measures. These disproportionately affect poorer nations and underscore health inequities.

Political instability and conflict make matters worse as they lead to population displacement, further poverty, and devastated infrastructure and health systems. Countries such as the DRC, Sudan, and Yemen are seeing cases spike as conflict forces people into areas without access to clean water or sanitation, and renders the health system largely nonfunctional.

And though not a direct cause of increased cholera risk, climate change has a similar effect, driving people out of their homes into overcrowded shelters with makeshift sanitation and poor hygiene, all while limiting access to care. Both South Sudan and the DRC have been experiencing flooding, affecting availability of clean water, sanitary environments, and basic health services. Both conflict and climate disasters make diagnosis and treatment become difficult, which can lead to serious illness and death.

Factors Driving Increased Cholera Risk

Source: Global Task Force on Cholera Control [site].

A recent report also confirmed the appearance of a cholera strain resistant to 10 antibiotics, including common treatments such as azithromycin and ciprofloxacin, in East Africa. Antimicrobial-resistant strains have contributed to recent years’ rampant outbreaks, and experts fear that additional resistance would compromise all available oral antibiotics. With diagnostic limitations in some of the most afflicted nations, patients may be treated with ineffective antibiotics, contributing to greater potential for antimicrobial resistance. With no new cholera treatments in the pipeline, this poses a massive risk in the efforts to control cholera outbreaks.

3 Top Takeaways

- Cholera cases and deaths continue to climb. June saw 62,330 cholera and/or acute watery diarrhea (AWD) cases and 527 deaths. Since the start of the year, there have been 305,903 cumulative cases and more than 3,500 deaths across 28 countries. The hardest hit regions are the Eastern Mediterranean, Africa, and South-East Asia.

- Conflict and climate change fuel increasing cholera cases. Resurging outbreaks of this vaccine-preventable disease are driven by conflict and climate change events such as floods and droughts, which limit access to clean water, sanitation, and healthcare access. One billion people are at risk of infection as outbreaks exceed the response capacity, including a drop in the emergency vaccine stockpile.

- Antimicrobial cholera strains compound challenges with disease control. Drug-resistant strains of cholera have been identified and are believed to be contributing to surging cholera cases. However, impaired diagnostic capacity in many affected countries means circulating strains are unknown and inappropriate treatments are being given — further worsening the issue of antimicrobial resistance.

Containing cholera calls for collaborative response

Cholera is a preventable disease. Of utmost importance in curbing spread is improved water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure. But funding gaps, both regionally and internationally, and lack of prioritization outside of emergency situations have allowed the bacterial disease to circulate beyond cholera-endemic regions. For example, only 16% of African countries have fully funded National Cholera Plans and 31% have implemented water quality interventions as country-level commitment remains variable.

Vaccine supply shortages, caused by increased demand and manufacturing constraints, are increasing vulnerability as populations go undervaccinated in both preventive and reactive settings. Between January 2023 and July 2024, 102 million doses of the Oral Cholera Vaccine were requested despite only 51 million doses produced amid complete depletion of the global stockpile. With last month’s stockpile at 2.9 million — far below the emergency stockpile threshold of 5 million doses — the global capacity to respond is stretched thin.

“There are just so many forces acting against cholera prevention,” says Andrea Thomas, PhD, BlueDot’s head of epidemiology. “But cholera is a solvable problem — it’s not out of our hands.” Despite confronting many ongoing outbreaks and limited resources, the Africa CDC has spearheaded the response to cholera, coordinating efforts from local and international bodies to work toward cholera elimination by 2030.

From calls for robust investment into WASH and timely access to prevention, diagnostic, and treatment measures, efforts are already beginning to materialize. Facilitated by the WHO, more than 50 institutions have formed the GTFCC to provide real-time data, centralize technical guidance and training resources, and offer country-specific support. With commitment to the 2030 cholera elimination roadmap, the prospect of a global cholera pandemic may be prevented.

On our radar

- Chikungunya in China: During a one-week window in late July, 2,940 new cases of chikungunya were reported in Guangdong province, bringing Guangdong’s total case count for the year to 4,824 as of July 26. The surge indicates ongoing mosquito-to-human transmission amid reports of strained public health infrastructure. Chikungunya’s regional spread has been confirmed in bordering Macau, where at least two exported cases have been reported, while the Hong Kong Centre for Health Protection enhances control point inspections. The presence of the Aedes albopictus vector underscores the risk of a wider outbreak.

- Acute Flaccid Myelitis in Gaza: Between May and July, 45 cases of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) were reported in Gaza. A syndrome marked by sudden limb weakness progressing to paralysis, AFP may signal undetected polio — a serious viral infection that affects the nervous system. The ongoing conflict and humanitarian crisis increase the risk for infectious disease spread and further health system collapse, which affects disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

- Malaria in Romania: A case of malaria was confirmed in Bucharest, Romania, on July 10 among a patient with no recent international travel history — potentially an indigenous case of the mosquito-borne illness. If found to be indigenous, this would be the first such case in over 60 years. By July 10, 21 travel-reported cases had been reported, increasing the risk of reintroduction in the nation. The source of infection is under investigation, as is the risk of broader transmission.

A final note

BlueDot’s biweekly newsletter, Outbreak Insider, is on summer holiday for the month of August. We know infectious diseases don’t stop circulating, so we’ll be back to get you caught up to speed in September. In the meantime, sign up here — we’ll see you in a few weeks refreshed and ready to bring the most important infectious disease news!