Twelve months since avian influenza was first detected on dairy farms, human cases have steadily increased in the United States, and may be reaching a tipping point

So far this year, five human cases of influenza A(H5N1) (colloquially referred to as bird flu when in animals) have been confirmed in the United States. That brings the total number of confirmed human cases in the country to 70 since the outbreak began in March 2024.

These laboratory-confirmed cases may only be the tip of the iceberg: recent studies have shown evidence of past undetected infections among veterinarians and other farm workers, meaning the true scope of avian influenza infections is likely much higher. From Washington and California to Texas, Wisconsin, and Ohio, avian influenza is spreading far and wide in birds and animals, with no signs of slowing down.

In some recent human cases, we have also seen a spike in the severity of disease associated with H5N1 infection, with at least four people hospitalized due to illness. Earlier this year, a patient in Louisiana died, marking the first H5N1 death in the USA. New evidence shows early signs that the virus may be adapting to better infect humans. No human-to-human transmission has been detected as yet, which is the primary reason why the threat to humans is still considered low. Nevertheless, the virus has proven itself dynamic and serious in a proportion of cases.

“Each avian influenza infection in humans increases the opportunities for viral mutations that could inch us closer to a public health emergency,” says Andrea Thomas, PhD, BlueDot’s head of epidemiology. “It’s like watching a potential pandemic emerge in slow motion.”

Previous editions of Outbreak Insider examined H5N1 in animals and explored valuable insights from experts at BlueDot. This edition will focus on avian influenza in humans and review preventive measures that can reduce the risk of sustained human-to-human transmission or the emergence of human adapted strains.

A brief overview of bird flu in humans

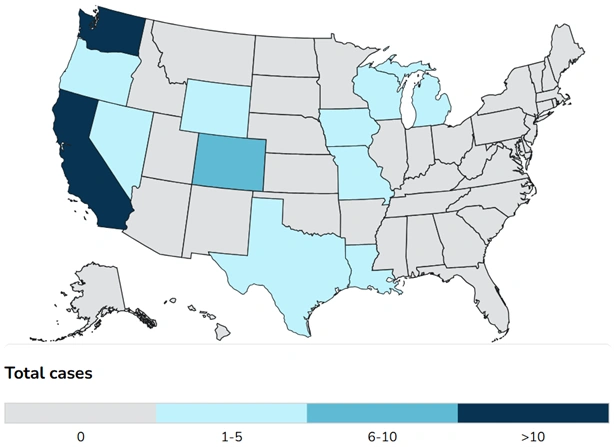

In March 2024, an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) erupted on dairy farms in the US. Not long afterward, the first human case was reported in Texas. At first, confirmed human cases hovered at three, with limited testing. But by the end of July, cases had doubled following a separate outbreak as a result of exposure to sick poultry. As the year came to a close, 65 people were confirmed positive for influenza A(H5N1), primarily driven by exposure to infected dairy cattle in California. Now, 70 human cases have been confirmed in 12 states across the nation so far.

Confirmed Human Cases of Influenza A(H5N1) Across the US Since 2024

Source: US CDC.

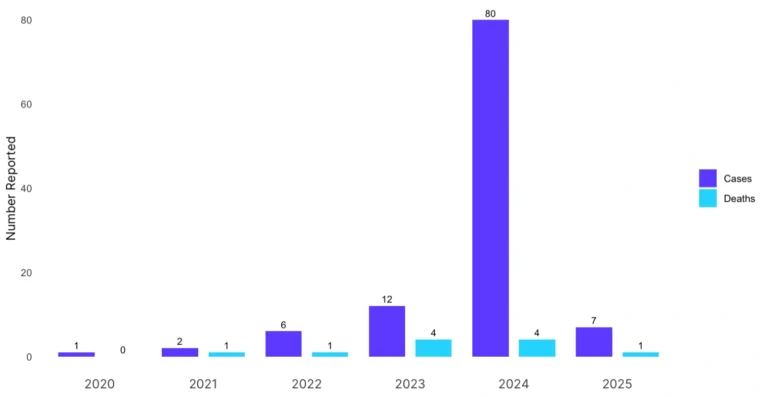

Last year, a total of 80 cases were reported around the globe, far outnumbering counts from previous years going back to 2016. Of those human cases, the US accounted for more than 80% of them, with cases also reported in Canada, Cambodia, China, Vietnam, and Australia. While hospitalizations and deaths have remained rare, within the last year there have been at least five hospitalizations in North America, one of which resulted in the death of a Louisiana resident at the beginning of 2025 following exposure to infected backyard poultry.

In addition to these confirmed cases, recent studies have pointed to the emergence of silent spread of influenza A(H5N1) among veterinarians and farm workers. In recent serological studies, anywhere from 2% to 8% of those tested showed antibodies that indicated recent prior infection, despite no known exposure or reported symptoms. This means that recorded case counts are likely underestimated, and the true incidence of avian influenza in humans is much higher than reported. Considering that the US poultry industry provides 2 million jobs alone, a substantial number of people are at risk of infection as outbreaks continue to occur in this sector – to say nothing of those who may be exposed through dairy sector employment, raw milk, or contact with other infected species.

Global Number of Influenza A(H5N1) Cases and Deaths by Year

Source: BlueDot Trends in Avian Influenza report, February 24, 2024

Among influenza A(H5N1) cases in humans, two genotypes have been predominantly identified in the United States: B3.13 and D.1.1. The B3.13 genotype is linked to infections in cattle and is behind most human cases. The D.1.1 genotype has been predominantly affecting wildlife in North America and is also responsible for outbreaks in captive wild birds and poultry.

Though it’s too early to say whether D.1.1 is a more severe genotype of H5N1, it has been observed to cause some severe infections in humans, including the deceased Louisiana resident, the previously hospitalized Canadian teenager, and more recently with the hospitalizations of the last two confirmed US cases. In the Louisiana and Canadian cases, lab analysis found that the same mutations in the virus were emerging in each patient – likely during the course of their infections— which allow the virus to more efficiently infect human cells.

Influenza A(H5N1) in humans usually results from spillovers, or exposure to the virus in animals. The current predominant avian influenza viruses circulating in the US have caused ongoing and widespread outbreaks in dairy cattle, poultry, wild birds, and other mammals such as small rodents. As of February 21, nearly 163 million poultry (since 2022) and 973 dairy herds (since 2024) have been affected across the country. Direct and indirect contact with infected animals or environments, as well as potential airborne transmission of the virus among animal populations, contribute to the spread of disease.

Recent evidence even suggests windborne transmission may be occurring among poultry, due to plumes of dust containing contaminated feces. And with non- comprehensive testing of other farm animals such as beef cattle or swine, the scope of the risk to humans is difficult to measure.

4 Top Takeaways

- Human influenza A(H5N1) infection has hit historic highs in the US. Since the outbreak began last year, one death and 70 human cases of avian influenza have been confirmed across the US. It is the largest outbreak of influenza A(H5N1) among humans in the country’s history — with no signs of slowing down.

- Undetected cases lead to underestimated case counts. Antibody studies have found evidence of past unknown infections among veterinarians and farm workers, indicating that case counts are likely much higher than previously realized. Undetected cases provide further opportunity for disease spread and adaptive mutations, or a reassortment with human influenza virus strains.

- Metamorphosis in H5N1 virus make-up. Two genotypes circulating in the US, D1.1 and B3.13, have been identified in humans. Analysis of the virus among those with severe illness, has found the emergence of mutations that may allow for more efficient infection in humans. Despite no human-to-human transmission, more severe disease increases risk for hospitalization and death, especially among those who are immunocompromised and/or have underlying conditions.

- Applying COVID-19 learnings for avian or novel influenza pandemic prevention. The effects of the current outbreak are being felt, as egg prices soar and flocks are culled at unsustainable rates. Vaccinations, enhanced surveillance and early detection, bolstered biosecurity measures, and public health campaigns are key to mitigate disease transmission.

How to halt H5N1’s public health threat

As the avian influenza outbreak intensifies and circulates undetected, the downstream effect on businesses and the economy continues to grow. As of November 2024, the bird flu outbreak had cost the US poultry industry more than $1.4 billion. Egg prices have skyrocketed to $8 USD per dozen, and depopulation practices are becoming unsustainable with 41.4 million domesticated birds culled in December 2024 and January 2025 alone. And as the virus shows signs of sporadic re-introduction in dairy herds from wild birds, and reinfected herds following an initial recovery, it appears that it is going to remain an ongoing issue.

Public health experts are encouraging proactive measures to prevent bird flu from becoming a greater risk to humans. Unlike other infectious disease outbreaks such as COVID-19 which rapidly emerged in humans, bird flu outbreaks are being studied while the virus mutates and spreads between species globally. There is an opportunity to take steps to stop a potential pandemic from happening. And yet, the current strategy to contain bird flu amongst domestic animal populations has not proven sufficient, underscoring a need for an adapted approach to get outbreaks under control.

A poultry vaccine for H5N2 has been conditionally approved by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), but vaccination of poultry is a short-term measure that comes with additional challenges in vaccine administration, as well as economic considerations. Given evidence of undetected infection among humans, spread between farms, and the required but unsustainable flock cullings, a vaccine may aid in containment where traditional biosecurity methods have fallen short. Vaccines for humans on the other hand have been stockpiled, but are not yet available to those with high exposure, while vaccines for livestock are in early-stage exploration.

Enhanced surveillance approaches, strengthened biosecurity protocols such as the proper and consistent donning of personal protective equipment (PPE), and public health education campaigns are other essential measures experts recommend. This could include the development of rapid tests that would allow for quick detection and containment of outbreaks among humans, especially those at elevated risk like farm workers and veterinarians. Further, efforts need to be made to reduce fear about stigmatization and economic repercussions so that the virus is not further transmitted.

Over the long-term, more substantial implementation of biosecurity measures, including adapted facility design, may be needed to minimize disease spread and outbreak frequency among animals. This may become especially important if additional evidence points to windborne transmission between farms. Reducing the outbreak risk among the poultry and dairy sectors would help to lower the risk to humans in the US.

“This is a good time to apply the lessons we learned during the COVID pandemic,” says Thomas. “Back then, observers often asked what we would do differently as a society if we’d had the time to prepare. Now we have that chance.”

On our radar

- Measles in Texas: The state is experiencing the largest outbreak of measles in 30 years as 93 confirmed cases and at least 16 hospitalizations have been reported. Emerging along the state’s western border, nine cases have also been reported in New Mexico. Beyond the Texas outbreak, other cases have also been reported in Alaska, California, Georgia, New Jersey, New York City, and Rhode Island, all largely attributable to low vaccination rates. Free walk-in vaccines, increased testing and contact-tracing, and community outreach are underway to mitigate disease spread.

- Dengue in Portugal and the Philippines: Two local cases of dengue have been reported in Madeira, Portugal. This marks the second local outbreak in the region since 2012-2013, when more than 1,000 cases were confirmed. Quezon City, the largest city in the Philippines, is also experiencing a dengue outbreak, with 1,769 cases and 10 deaths reported since the start of the year as of February 14. Compared to last year, cases are up 200% in the city and 40% nationally. Both countries are strengthening public health measures, including dengue prevention and control campaigns and the elimination of mosquito breeding sites.

- Unknown Illness in the DRC: Approximately 431 cases and 53 deaths have been reported following detection of two separate outbreaks this year in Équateur province in the northwest Democratic Republic of the Congo. The second cluster has seen rapid disease progression with high fatality; 50% of deaths have occurred within 48 hours of symptom onset. Concurrent outbreaks and ongoing humanitarian crises are affecting outbreak control. Surveillance is underway to identify the cause as Ebola and Marburg have been ruled out, while recently some tests have come back positive for malaria.

BlueDot is a trusted and unbiased source offering timely updates for avian influenza and over 190 other infectious diseases. To receive global and local outbreak intelligence, sign up here to receive every edition of BlueDot’s biweekly newsletter, Outbreak Insider.